The relationship between religious proselytism and development is sharply contested. International covenants recognize that religious freedom includes rights to personal religious conversion and public religious witness. But critics claim that proselytism can violate the rights of affected communities to maintain their traditions and can sow division in fragile societies. This week, Cornerstone asks writers to discuss the social, political, and economic consequences of proselytism.

By: Brian Grim

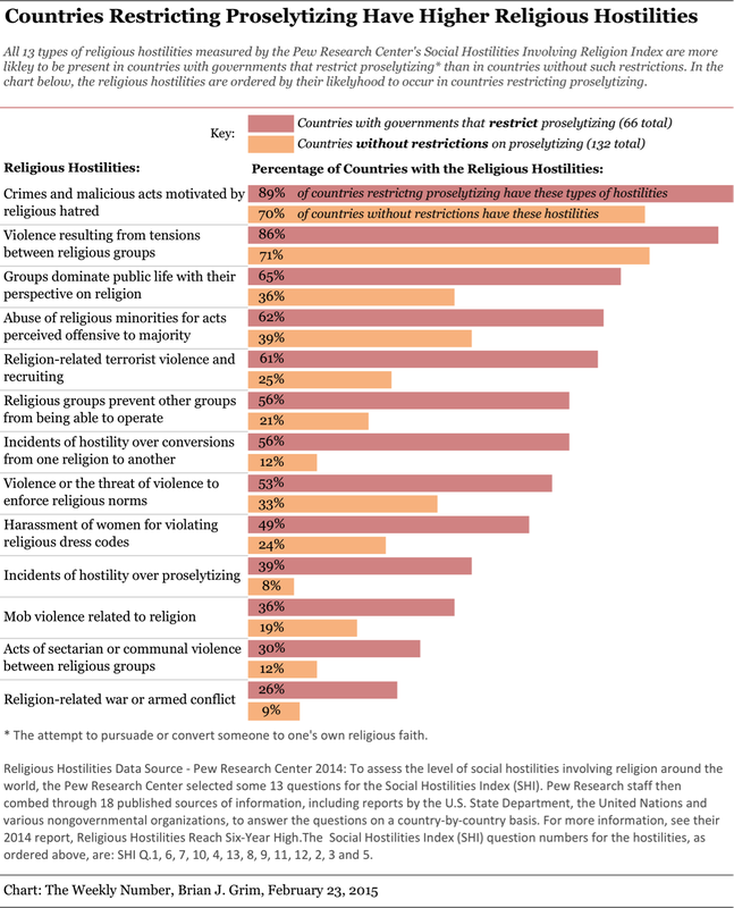

A new analysis by the Weekly Number shows that religious hostilities are consistently more likely to occur in countries where governments restrict proselytizing than in countries without such restrictions. For instance, looking at Pew Research data , hostilities over proselytizing are five times more likely in countries with laws restricting proselytism than in countries with no such restrictions. Also, hostilities over conversions are more than four times as likely in countries with laws restricting proselytism as in countries without restrictions. (See data here and at the bottom of this post.)

These findings are notable because often the justification given for laws restricting proselytism is to prevent religious unrest. Part of the unease with “proselytism” is that the term itself has taken on a negative connotation. In its neutral form, it simply means sharing one’s faith with others in an attempt to convince them to join your faith or belief. In this way, it is like any discussion where one person tries to get another to see the truth of his or her position.

But objections to proselytism sometimes stem from being associated in the minds of some with either unwelcome preaching or coercive argument. And in some cases, accusations of forced conversions or even purchased conversions are associated with the term proselytization.

Certainly, coercion in matters of religion should be resolutely rejected. But there are non-coercive missionary endeavors that people may still find objectionable. For some, proselytism is viewed as an intrusion into matters that are personal or cultural. In that way, it might be like an advertisement or argument from a company or political party one finds disagreeable. As long as you can change the station or turn the television off, then presumably no harm, no foul.

One of the most common faces of proselytism are the 75,000 young Mormon men and women volunteering as missionaries throughout the world with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS). On the one hand, in conversations with many former Mormon missionaries, some point to experiencing negative reactions to their proselytizing mission espousing a restored Christianity. Certainly, many parents who send their children off on their two-year missions have a dose of apprehension for the reception their children might face. But overwhelmingly, LDS missionaries report positive experiences, and it’s not uncommon for former missionaries to return to the places they served around the world later in life to do business or other forms of service. (For a Mormon perspective on their missionary work, see the last vignette of a missionary mom in the recent film, Meet the Mormons.)

While Mormons might be a visible missionary force, the two largest religions—Christianity and Islam in their various forms—are proselytizing faiths fielding hundreds of thousands of missionaries.

So, why might proselytizing be associated with lower religious hostilities? There are a number of plausible reasons, but I will name just three. First, religious hostilities tend to be highest when governments restrict religious freedom, which includes proselytism, as was established in my articles and book with Penn State professor Roger Finke. In The Price of Freedom Denied, we demonstrated that restrictions on religious freedom often accrue to the benefit of monopolistic religions and coercive governments. By contrast, when religious freedom is protected and people are free to persuade others of their beliefs, societies have a rich pluralism that gives space for moderate voices within religions.

Second, proselytism adds to this pluralism and moderation by taking religion from the shadows where violent extremism tends to grow and putting it into the public spotlight. Indeed, as I have argued, it is important for people of various faiths to engage people at risk of extremist radicalization with other faith arguments. To the extent that violent extremism feeds on the lack of informed religious understanding, proselytizing is one mechanism through which diverse and arguably less violent forms of religion can be explored. To be clear, I’m not advocating proselytism as a strategy to counter violent extremism, but certainly few would disagree that people lured down that path of radical violence need to be converted to a more peaceful and productive perspective.

And third, research by political scientist Robert Woodberry demonstrates historically and statistically that proselytizing Protestants heavily influenced the rise and spread of stable democracy around the world. His recent article in the American Political Science Review shows that such missions were a crucial catalyst initiating the development and spread of religious liberty, mass education, mass printing, newspapers, voluntary organizations, and colonial reforms, thereby creating the conditions that made stable democracy more likely. In a similar way, as proselytizing missionaries encounter human need, they are often the people on the ground calling for response. This ranges from Southern Baptists helping to bring in disaster relief, to Ismaili Muslim missionaries tied to the great humanitarian resources of the Aga Khan Development Network.

What about Catholics?

For Catholics, Pope Francis caused quite a stir when he said that the Lord “has invited us to preach, not to proselytize.” To some, they may seem the same. But in his mind, they are apparently quite distinct. Citing Benedict XVI, he said that “the Church grows not to proselytize, but to attract.” And this attraction, he said, comes from the testimony of “those who proclaim the gratuity of salvation.”

Pope Francis also said during a weekly Sunday Angelus, addressing the skeptical in the crowd, that “the Lord is calling you to be a part of His people and He does it with great respect and love. The Lord does not proselytize; He gives love. And this love seeks you and waits for you, you who at this moment do not believe or are far away. And this is the love of God.” Pope Francis prayed that “all the Church” may be steeped in “the joy of evangelizing,” invoking the aid of the Virgin Mary so that “we can all be disciple-missionaries, small stars that reflect His light.”

Brian J. Grim is president of the Religious Freedom & Business Foundation and a leading expert on the socioeconomic impact of restrictions on religious freedom and international religious demography.

This piece was originally authored on February 23, 2015 for the Weekly Number. It was then re-posted with the author’s permission on March 6, 2015 for the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

THE RFI BLOG

Does Southeast Asia Lead the World in Human Flourishing?

RFI Leads Training Session on Religious Freedom Law and Policy for U.S. Army War College

Oral Argument in Charter School Case Highlights Unconstitutional Motives Behind OK Attorney General’s Establishment Clause Claim

Largest Longitudinal Study of Human Flourishing Ever Shows Religion’s Importance

Keys To Human Flourishing: Faith And Relationships Outweigh Wealth

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Reaffirming Religious Freedom: Bridging U.S. Advocacy and Iraq’s Constitutional Framework

Political Polarization, Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty

Bridging the Gap Between International Efforts and Local Realities: Advancing Religious Freedom in the MENA Region

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action