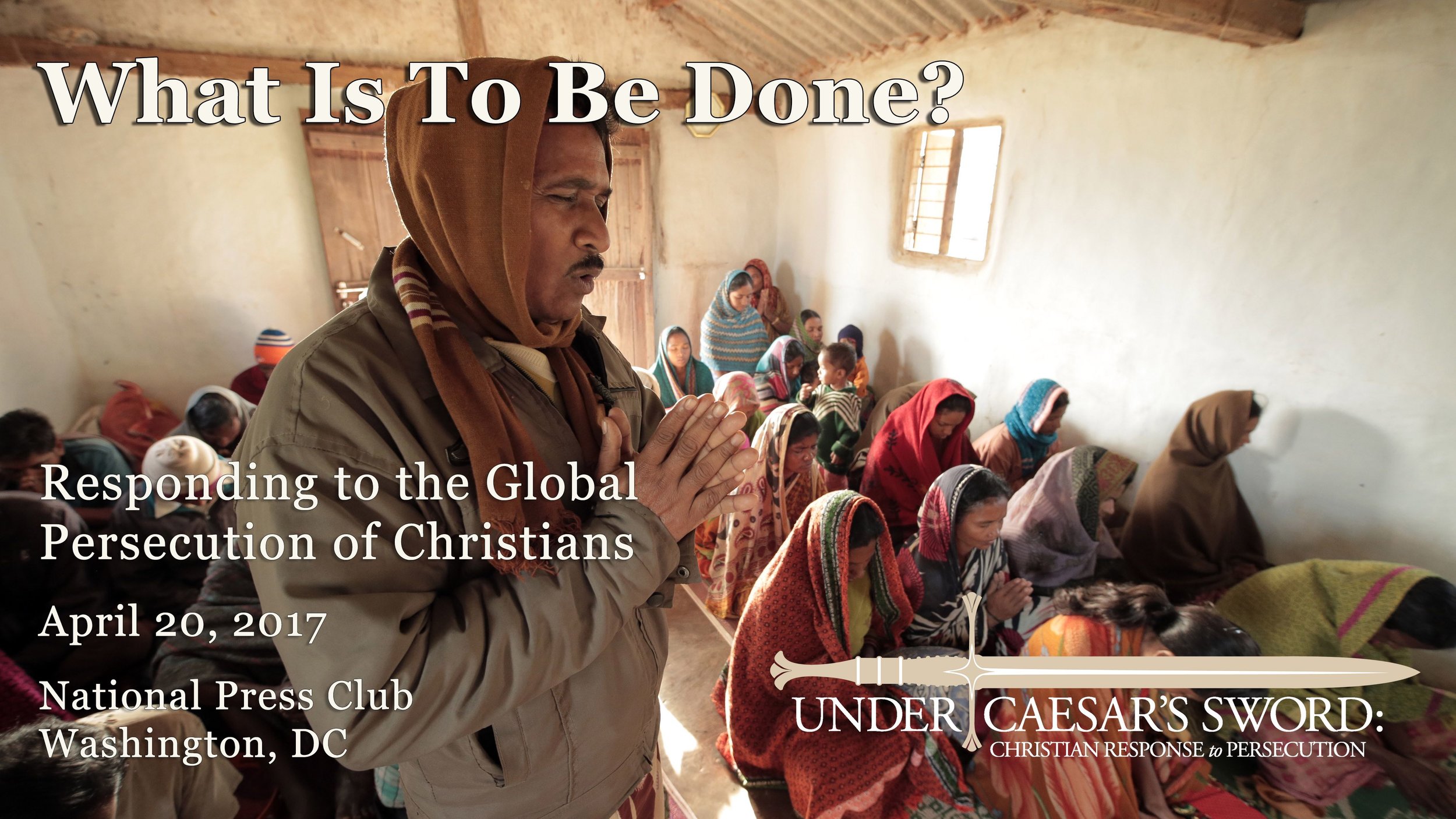

Under Caesar’s Sword is a three-year, collaborative global research project by a team of scholars to investigate how Christian communities respond when their religious freedom is severely violated. A public report with the findings of this project will be launched at the Public Symposium: What is to be Done? on April 20, 2017 in Washington, D.C.

This series of blog posts draws from scholars’ research, personal reflections, and responses to current situations of religious persecution. See all posts in the series: Reflections on Under Caesar’s Sword

This article originally appeared as the introductory essay to a special volume of The Review of Faith & International Affairs Volume 15, 2017 – Issue 1: UNDER CAESAR’S SWORD: HOW CHRISTIANS RESPOND TO PERSECUTION. It has been edited for length and reposted here with permission of the author.

The year 1917, exactly one century ago, was a critical one in the history of the persecution of Christians. Two revolutions empowered regimes that brutally violated religious freedom. The Russian Revolution yielded the communist Soviet Union, which heavily purged the Russian Orthodox Church along with the Ukrainian Catholic Church and Protestant churches as well as Jews and Muslims. The Mexican Revolution brought to power an anticlerical regime that harshly repressed the Catholic Church and, in the mid 1920s, killed hundreds of priests and other Catholics. These revolutions created thousands of martyrs and inaugurated a century in which more Christians lost their lives to persecution than in all other centuries combined.[1]

How Christians respond to persecution is the subject of the project, Under Caesar’s Sword, whose findings are showcased in the essays in this symposium. By now, the contemporary persecution of Christians has been documented through several books, the demographic work of David Barrett and Todd Johnson, the Church of San Bartolomeo, and monitoring groups like Aid to the Church in Need and Open Doors.[2] This persecution has been studied, but it remains underreported by the mainstream media and human rights groups.

Far less well understood is how Christians respond when their religious freedom has been severely violated. Under Caesar’s Sword is the world’s first global investigation of these responses and is undertaken on the premise that a systematic understanding of them can help those who live in relative freedom practice stronger and more effective solidarity with persecuted Christians and can help the often-isolated victims of persecution understand better what responses they might undertake.

Launched in fall 2014 by a grant of $1.1 million from the Templeton Religion Trust, the project is carried out by a team of 15 scholars who have studied Christian responses in 25 countries as well as The West and Latin America. Their results were first presented at an international conference in Rome in December 2015, one of whose main events was a memorial prayer service at the Church of San Bartolomeo. Under the auspices of Notre Dame’s Center for Ethics and Culture, Georgetown’s Religious Freedom Research Project, and the Religious Freedom Institute, the project has produced a documentary film, while Forthcoming are an edited volume of scholarly essays, a public report, and curricula for schools and churches are soon to appear. The website of Under Caesar’s Sword contains detailed information about the project. See usc.nd.edu. For the film, see http://ucs.nd.edu/film/

Christians are not the only people who suffer from egregious violations of their religious freedom, and they have inflicted their own share of persecution, especially in episodes between the 4th and 17th centuries. There is much evidence, though, that today it is Christians who suffer the largest share of religious persecution. Estimates vary considerably and unambiguous data is virtually impossible to come by, but even the most cautious figures place the proportion of religious persecution that Christians experience at 60 percent or above. The International Society for Human Rights, a secular NGO based in Frankfurt, estimated in 2009 that Christians experience 80 percent of all acts of religious discrimination in the world, a finding that separate human rights observatories corroborate. This, combined with the underreporting of Christian persecution, warrants this study.

In the remainder of this introductory essay, we depict the contours and implications of the responses to persecution that the scholars have discovered.

Varieties of Religious Persecution

Despite an overwhelming focus in the media and the popular Christian imagination on violent Islamist persecution and severe totalitarian repression in countries such as China, the global persecution of Christians assumes a vast variety. The swords of many Caesars hang threateningly over Christian communities all over the world. The regimes in which persecution occurs are highly diverse. They comprise not merely brutal authoritarian regimes and failed states but also relatively stable and well-established electoral democracies such as India and Sri Lanka, whose very democratic structures incentivize groups to target Christian minorities in order to solidify the political support of non-Christian majorities.

According to an analysis by Marshall[3], Christian persecution in the world occurs mainly in five very different contexts: (1) Communist regimes (China, Vietnam, Laos, North Korea, and Cuba); (2) authoritarian and national security states; (3) South Asian countries influenced by religious nationalism; (4) Muslim-majority countries; and (5) Western countries influenced by secularism (or what legal scholar Steve Smith calls “secular egalitarianism”.[4]

Similarly, persecution assumes very different forms. In a number of contexts, the full machinery of state power brings down the iron fist of persecution in the form of direct and appalling violence: police and security services, often directed by bureaus of religious affairs, forcibly break up church services and Bible studies, and imprison and torture pastors, evangelists, and ordinary church members for engaging in ordinary religious activities. In some of the same contexts but in others as well, the iron fist wears a velvet glove. Alexis de Tocqueville limpidly observed that 19th-century white Americans dispossessed and subjugated native peoples “with wonderful ease, quietly, legally, philanthropically,” adding that “[i]t is impossible to destroy men with more respect to the laws of humanity.” It is striking how much state persecution of Christians throughout the world is conducted with similar legality, regularity, and bureaucratic propriety.[5] As Roger Finke, Dane R. Mataic, and Jonathan Fox observe, a growing number of regimes impose—with manifest intentionality—a thicket of registration requirements so onerous that the otherwise simple business of instituting a Christian organization, buying property for Christian purposes, or building a Christian house of worship becomes effectively impossible.[6] On the other hand, much Christian persecution—whether visited by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria or Islamist militias in Indonesia’s Maluku islands or Buddhist militants in Sri Lanka—arises from non-state actors, whether formal or informal. Persecution by such groups is often brutally violent. At the same time, as Brian Grim and Roger Finke have shown, there is often a correlation, and in many instances close causal interaction, between government restriction and social hostilities directed against Christians.[7] For example, it is clear that in many cases non-state persecution “from below” depends on the direct support (in financing or active encouragement) or indirect help (in providing an environment of impunity) of government institutions or state officials working “from above.”

In short, the overall upturn in the magnitude, direction, and geographic breadth of global Christian persecution is grim. Christian persecution takes place across a geographic band of enormous length and breadth—more or less co-extensive with what Eliza Griswold has described as the world’s “tenth parallel” of religious conflict—that stretches from Libya, moves southw

ard to northern Nigeria, moves eastward to Egypt and the rest of the Middle East, expands north to Russia and south to Sri Lanka, and then proceeds eastward to China, Indonesia, and North Korea.[8] Based on systematic demographic analysis, Todd Johnson estimates that some 500 million Christians—more than 20 percent of Christians on earth—live in countries where they are likely to face severe persecution, with virtually all of them in this geographic band. By 2020, Johnson predicts, this figure will rise to 600 million, or nearly a quarter (23.5 percent) of the world’s Christian population.[9]

Varieties of Christian Response to Persecution

One of the most important fruits of our research was a categorization of the vast array of Christian responses to persecution our scholars observed and analyzed across the world. Three broad categories of response emerged, arrayed on a continuum from reactive to proactive: (1) survival strategies; (2) association strategies; and (3) confrontation strategies. In pursuing strategies of survival, Christians focus on preserving their communities and, if possible, their basic institutions and practices. In association strategies, Christians reach beyond survival to focus on building relationships and networks with groups outside their immediate communities—other Christians, non-Christians, and international actors—to enhance resiliency and mount some broad-based though relatively non-confrontational resistance to persecution. In strategies of confrontation, persecuted Christian communities focus on mounting direct and overt forms of resistance and challenge to those government or societal actors engaged in persecution. Among the cases we analyzed, we found that survival-focused strategies are most common, association strategies are widespread but somewhat less common, and confrontation strategies are least prevalent.

Two words of caution are in order here. First, words such as “overt,” “minimal,” or “assertive” imply no moral judgment of Christian responses to excruciatingly difficult circumstances. Sometimes a survival-focused strategy that involves relatively minimal overt resistance to persecution and its perpetrators—such as a focus on continuing to worship and gather in community—involves deliberate effort, courage, and determination and can be heroic in some circumstances, for instance, the war and violent Islamist repression that characterize Syria and Iraq today. We offer our typology not to deliver normative judgments but to advance clarity and understanding about what Christians do—and what they might do—when they are under fire. Second, persecuted Christian communities can and do frequently undertake more than one strategy. For example, a number of unregistered house churches in China, such as the Shouwang Church in Beijing, have engaged in all three strategies in recent years, more or less simultaneously.

To clarify, what differentiates these strategies from each other are three main factors. One factor that differentiates them is the immediate object or goal of the strategy. Another is the kind of activity the strategy involves. And the third is the degree of direct, intentional engagement with systems and perpetrators of persecution.

In survival-oriented strategies, the response of Christians to persecution is to invest maximum energy and resources in activities that advance the simple goals of survival and subsistence—from one day to the next, at a minimum, or from one generation to the next, if possible. Under some conditions, a focus on survival will require flight. Under other conditions, it may be possible to remain in a context of persecution, though in a posture that is hunkered down and focused on putting down social roots in the form of underground networks and institutions. In this kind of strategy, persecuted Christians keep to an absolute minimum any direct engagement with and avoid any direct challenge to the perpetrators and structures of persecution.

In strategies of association, the response of Christians to persecution is to invest the preponderance of available energy and resources in activities that build formal and informal relationships and patterns of cooperation with those outside of their persecuted communities who may sympathize with their plight. These others may be within or outside their country’s borders. While strategies of association also seek to ensure survival, their main goal is to build longer-term resiliency and capacity to resist or mitigate persecution through robust relationships with other Christians as well as with sympathetic non-Christians. In this strategy, too, direct engagement with those responsible for persecution is kept to a minimum because the focus is not so much on opposing or resisting persecution as on building the capacity (sometimes through dialogue, sometimes through coalition-building) to resist persecution from a stronger and broader position.

Finally, in strategies of confrontation, the focus is on mounting activities that directly criticize, challenge, or de-legitimate the perpetrators of persecution, with the goal of weakening or even eliminating Christian persecution at its source. Here, of course, direct, overt, and often confrontational engagement with the perpetrators and structures of persecution is at a maximum.

Conclusions

Do any generalizations emerge from this study of Christian responses to persecution? Each category of response—survival, association, and confrontation—contains exemplary responses as well as misfires and approaches whose effects are highly uncertain. Might any contours be spotted in the data, though?

We venture at least one observation, which began to emerge in the foregoing analysis. Surprisingly rare are the kinds of responses that have achieved fame through movies, documentaries, and international media stories: the high-profile martyrdom, the prophetic denunciation, the acclaimed prisoner of conscience, or the band of Christians taking up arms. Neither sexy nor scary, the bulk of responses rather takes the form of “creative pragmatism,” involving short-term efforts to ensure security; build capacity and strength through ties with other churches, religions, and secular actors; and sometimes oppose the government through protest or legal channels. To some observers, such a conclusion will seem pedestrian: is there not something more dramatic to be found?

The pragmatism of these efforts, though, should not obscure the creativity, courage, nimbleness, and theological conviction that often attend them. Christian communities take up strategies of survival and association to fortify themselves in the short term but often with the long-term conviction, grounded in their faith, that if they can hold out, a sunnier day will come—not only in the next life but in earthly time. On this day, one that members of these communities may not live to see, the persecuting regime will fall or the militant group will evanesce, and the church will then deepen its roots and expand its branches.

This very kind of hope motivated the church of the early centuries of Christianity under the Roman Empire. Christianity was generally outlawed and Christians suffered persecution that was periodic and eventually swelled into the rampant, empire-wide crackdowns of the third and early fourth centuries. Yet, while the period certainly has its famous martyrs, it was common for Christian communities to seek accomm

odations with local officials that allowed them to survive, worship, conduct the affairs of their communities, and even expand their ranks. Over these centuries, Christian communities not only survived but also grew at remarkable rates. Finally, just after the close of the period’s most repressive purge, the Diocletian Persecution, the Roman Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and declared freedom not only for Christians but also for all people through the so-called Edict of Milan of 313.[10] Thereafter, Christianity was poised to expand and to build a civilization. A similar long-term hope has motivated Christian churches in China, who survived and even expanded under the eradicationist policies of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1979) and who persist under the renewed repression of today. Such a hope can be found, too, in many other churches mentioned in the essays that follow.

This conclusion turns out to be far less pedestrian than it may seem to be at first sight and contains lessons for persecuted churches and for all those who would act in solidarity with them. Repeated persistently and sustained determinedly, short-term pragmatic responses can add up to a formidable long-term strategy. It is a strategy for which Christianity, built on a long-term hope, is uniquely suited.

Daniel Philpott is Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, and Co-Director of Under Caesar’s Sword: Christian Responses to Persecution. His books include Just and Unjust Peace: An Ethic of Political Reconciliation (Oxford University Press, 2012), and The Politics of Past Evil: Religion, Reconciliation, and the Dilemmas of Transitional Justice (University of Notre Dame Press, 2006). He is also a Contributing Editor on The Review of Faith & International Affairs.

Timothy Samuel Shah is Research Professor of Government at Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion, Director for international research at the Religious Freedom Research Project at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs, and a Senior Advisor with the Religious Freedom Institute. Shah is author of Even if There is No God: Hugo Grotius and the Secular Foundations of Modern Political Liberalism (Oxford University Press, forthcoming in 2017) and, with Monica Toft and Daniel Philpott, God’s Century: Resurgent Religion and Global Politics (W.W. Norton, 2011). He is also editor, with Allen Hertzke, of the two-volume study, Christianity and Freedom (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[1]Barrett, David, and Todd Johnson. 2001. World Christian Trends, AD 30—AD 2020. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library. [Google Scholar]

[2] 2013Allen, John L., Jr. 2013. The Global War on Christians: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Anti-Christian Persecution. New York: Image. [Google Scholar]; Marshall, Gilbert, and Shea 2013Marshall, Paul, Lela Gilbert, and Nina Shea. 2013. Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. [Google Scholar]; Shortt 2012Shortt, Rupert. 2012. Christianophobia: A Faith Under Attack. London: Rider Books. [Google Scholar])

[3] Marshall, Paul. 2016. “Patterns and Purposes of Contemporary Anti-Christian Persecution.” In Christianity and Freedom: Volume 2, Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Allen Hertzke and Timothy Samuel Shah, 58–86. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]),

[4] Smith, Steven D. 2014. The Rise and Decline of American Religious Freedom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.[CrossRef], [Google Scholar]

[5] Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1988 [1835, 1840]. Democracy in America. Translated by George Lawrence and edited by J. P. Mayer. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar][1835Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1988 [1835, 1840]. Democracy in America. Translated by George Lawrence and edited by J. P. Mayer. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]], 339.

[6] Finke, Roger, Dane R. Mataic, and Jonathan Fox. 2016. “Assessing the Impact of Religious Registration.” Presented to the U.S. State Department—Office of International Religious Freedom, February.

[7] Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2011. The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar].

[8] Griswold, Eliza. 2010. The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches from the Fault Line between Christianity and Islam. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

[9] Johnson, Todd. 2016. “Persecution in the Context of Religious and Christian Demography, 1970–2020.” In Christianity and Freedom: Volume 2, Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Allen Hertzke and Timothy Samuel Shah, 13–57. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

[10] Digeser, Elizabeth, “Lactantius on Religious Liberty and His Influence on Constantine.” In Christianity and Freedom: Volume 1, Historical Perspectives, edited by Timothy Samuel Shah and Allen Hertzke, 90–102. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]; WIlken, Robert. 2016. “The Christian Roots of Religious Freedom.” In Christianity and Freedom: Volume 1, Historical Perspectives, edited by Timothy Samuel Shah and Allen Hertzke, 62–89. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar].

**All views and opinions presented in this essay are solely those of the author and publication on Cornerstone does not represent an endorsement or agreement from the Religious Freedom Institute or its leadership.**

THE RFI BLOG

Does Southeast Asia Lead the World in Human Flourishing?

RFI Leads Training Session on Religious Freedom Law and Policy for U.S. Army War College

Oral Argument in Charter School Case Highlights Unconstitutional Motives Behind OK Attorney General’s Establishment Clause Claim

Largest Longitudinal Study of Human Flourishing Ever Shows Religion’s Importance

Keys To Human Flourishing: Faith And Relationships Outweigh Wealth

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Reaffirming Religious Freedom: Bridging U.S. Advocacy and Iraq’s Constitutional Framework

Political Polarization, Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty

Bridging the Gap Between International Efforts and Local Realities: Advancing Religious Freedom in the MENA Region

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action