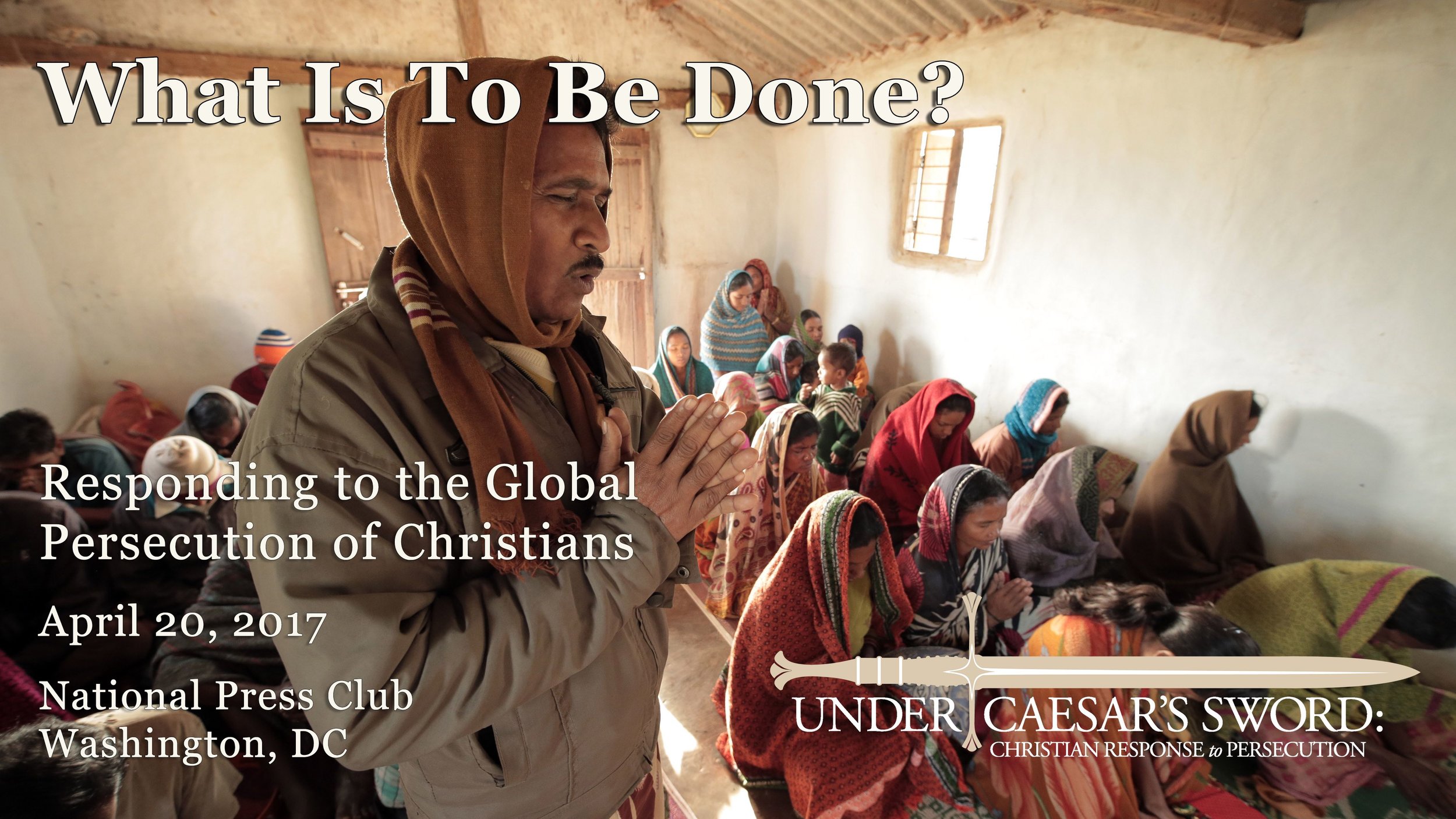

Under Caesar’s Sword is a three-year, collaborative global research project by a team of scholars to investigate how Christian communities respond when their religious freedom is severely violated. A public report with the findings of this project will be launched at the Public Symposium: What is to be Done? on April 20, 2017 in Washington, D.C.

This series of blog posts draws from scholars’ research, personal reflections, and responses to current situations of religious persecution. See all posts in the series: Reflections on Under Caesar’s Sword

To be sure, Christians in Iraq and Syria have been persecuted because of their faith during the last decade and a half, but they and their neighbors have also suffered simply because of the sectarian violence, civil war, and anarchy which have engulfed the entire region. The Syrian civil war alone has produced between 400,000 and 500,000 deaths, over 4.8 million registered Syrian refugees, and over 6.3 million IDPs.

The overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2003 fueled violent sectarian conflict and opportunities for the expansion of violent Islamic extremism. Over the next few years, conditions evolved which were devastating for the Christians in the country.

Matthew Barber has summarized well the fate of Iraqi Christians in the wake of the overthrow of Saddam Hussein:

Attacks on Christians occurred across the entire breadth of the country, from Basra to Mosul. Christians were routinely terrorized with bombings of churches, targeted vandalism of Christian businesses, bomb and mortar attacks on Christian houses, and frequent instances of kidnapping and rape. Christians were killed inside their homes, while on their way to school, and while working in their shops. Christians employed by U.S. companies, including women, were specifically targeted, often while traveling to work. (research done for the Under Caesar’s Sword project, and published in in Christianity and Freedom, Vol. II: Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Allen D. Hertzke and Timothy Samuel Shah, 455)

Following the fall of Mosul, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi declared in late June 2014 the arrival of a caliphate and the “Islamic State.” The opportunities to implement more broadly a policy of what the State Department would call in March 2016 “genocide” (against Christians, Yezidis, and Shia) expanded markedly.

The civil war in Syria, from the spring of 2011, likewise created a perfect storm of conditions conducive to the expansion of violent Islamic extremism – conditions which inevitably deeply compromised the security of Syria’s Christian populations.

How have Christians in Iraq and Syria responded to the persecution, conflict, and anarchy, and why have they chosen which response? Why one response is chosen over another is invariably a complicated and sometimes mysterious interplay between that which they can control and that which they cannot. At different times, different responses are called for.

Sometimes Christians have sought to lie low, hoping the storms of the present will just pass them by. Some have sought to pay the jizya or “head tax” (which, in fact, in contrast to the Ottoman past, has been nothing but, as Nina Shea has pointed out, “naked extortion” designed to drive the Christians out). Occasionally, Christians have taken up arms to defend themselves. Some have resorted to an uneasy “de facto” alliance the brutal dictator Assad (fearing their fate will almost certainly be worse if the jihadists assume power).

Sometimes Christians have sought to bear witness by staying put, by seeking to reflect an unshakeable faith that though they may die, the Faith will not. As Father Ragheed Ganni from Mosul put it before his own martyrdom in 2007: “We empathize with Christ, who entered Jerusalem in full knowledge that the consequence of His love for mankind was the cross.” (cited in Mindy Belz, They Say we are Infidels, 296)

It is quite clear, however, that the major response of Christians in Iraq and Syria to Christian persecution, and to conditions of war and conflict, has been to become refugees or IDPs. It can be noted, of course, that in sheer numbers, the Muslim victims of ISIS are greater than are Christian victims, for the ISIS intolerance is also directed at Muslims who they consider “kafir,” or “apostates,” such as the Shia, but their rage is also directed at the majority Sunnis if they will not accept their ideology or rule. However, Islam is not in danger of disappearing from Iraq and Syria – Christianity’s future, on the other hand, hangs by a thread.

Iraq has experienced the steepest proportionate decline of Christianity of any country in the Middle East in recent years. It is estimated that there were 1.5 million Christians in Iraq at the time of the US invasion in 2003 (just under 6 percent of population). Prior to the rise of ISIS in 2014, the community had shrunk to less than 500,000 and now that number has probably declined to between 100,000 and 300,000 (less than one percent of the current Iraqi population). Many of the latter are IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq (governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government, KRG).

Though there has been a significant Christian exodus from Syria since the beginning of the civil war in the spring of 2011, in fact, the Christian population has been in decline there since the beginning of the twentieth century. The percentage of Christians in Syria was estimated to have been more than 25 percent of the population in the early 20th century, but fell sharply as a result of post-World War II mass migration. The Christian share of the population has dropped from 15 percent in 1970 to no more than 5 percent in 2015.

In the spring of 2016, Antoine Audo, the Chaldean Bishop of Aleppo, reported that Syria’s Christian population had declined from 1.5 million to 500,000, and it is even less a year later.

And what are the consequence of flight, the most prevalent response by Christians in Iraq and Syria to the persecution and turmoil of the last decade and a half? Beyond the suffering of those who remain, and those who find themselves suffering in refugee or IDP camps, there is the prospect of an Iraq and Syria devoid of its Christian population. And this is against a backdrop of an exodus of Christians from the Middle East that extends back to the beginning of the twentieth century. A similar departure of Jews from Iraq occurred in the middle of the twentieth century – partly a result of anti-Semitism, partly because of the founding of the modern state of Israel.

Today, of the 30 to 35 million worldwide Middle Eastern Christians, less than half still live in the Middle East. One hundred years ago, the percentage of Christians in the Middle East was 13.6 percent. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2010 of a total population of 341 million in the Middle East and North Africa, Christians made up just 3.7 per cent or 12.7 million, and that percentage has certainly dropped further by 2017.

The existential crisis of the moment, however, is in Iraq and Syria, though matters are getting much more tenuous in Egypt as well. The mass exodus of Christians needs to end if a healthy pluralism and multi-religious Middle East is to survive, but this will require ultimately an end to the civil war in Syria and the emergence in both Iraq and Syria of states which genuinely respect the rights of minorities. In the short term, security and economic opportunities must be secured for those who wish to return to their homes, even if ISIS is defeated in the short term, for otherwise a return will not occur, and the exodus will continue.

The very hard work of countering violent Islamic extremism must be undertaken in partnership with Muslims who are also are dramatically threatened by this movement which insists on calling itself “Muslim.”

Finally, we must all recognize, that as bad as violent Islamic extremism is, there are other lethal enemies of pluralism, human rights, and religious freedom in the Middle East which must be dealt with: brutal authoritarian regimes (which may call themselves secular, or wear vestiges of religious ideology) and intolerant ethnic or religious nationalism.

There is no question that the fate of Christians in Iraq and Syria at the present time hangs by a thread. It will take concerted efforts over both the immediate future and over the long term if Christianity is to regain a foothold in its ancient homeland.

Kent Hill is the Executive Director and Director of the Middle East Action team at the Religious Freedom Institute. He is a scholar on the Under Caesar’s Sword project investigating Christian responses in Iraq and Syria.

Under Caesar’s Sword is a three-year, collaborative global research project that investigates how Christian communities respond when their religious freedom is severely violated. A public report with the findings of this report will be launched at the Public Symposium: What is to be Done? on April 20, 2017 in Washington, D.C.

**All views and opinions presented in this essay are solely those of the author and publication on Cornerstone does not represent an endorsement or agreement from the Religious Freedom Institute or its leadership.**

THE RFI BLOG

Does Southeast Asia Lead the World in Human Flourishing?

RFI Leads Training Session on Religious Freedom Law and Policy for U.S. Army War College

Oral Argument in Charter School Case Highlights Unconstitutional Motives Behind OK Attorney General’s Establishment Clause Claim

Largest Longitudinal Study of Human Flourishing Ever Shows Religion’s Importance

Keys To Human Flourishing: Faith And Relationships Outweigh Wealth

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Reaffirming Religious Freedom: Bridging U.S. Advocacy and Iraq’s Constitutional Framework

Political Polarization, Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty

Bridging the Gap Between International Efforts and Local Realities: Advancing Religious Freedom in the MENA Region

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action