2022 Cornerstone Series on Translating Diplomatic Engagement to On-the-Ground Improvements in Religious Freedom

The 2022 International Religious Freedom Summit, hosted in Washington, D.C., and the 2022 Ministerial to Advance Freedom of Religion or Belief, hosted by the United Kingdom, are among the most significant international events focused on advancing religious freedom globally. They bring together governments, religious leaders, survivors of persecution, advocates, and civil society organizations from around the world to grapple with religious freedom challenges and opportunities.

The events illustrate the role of robust diplomatic engagement—inclusive of state or government actors, civil society organizations, and individuals—in advancing religious freedom and associated rights in diverse countries and contexts. But how do we ensure engagement in diplomatic efforts like the Summit and Ministerial lead to practical and sustainable improvements in religious freedom for communities in participating countries?

This Cornerstone Forum series invites experts to reflect on their experiences in efforts to advance religious freedom globally, engage key stakeholders in the process, and safeguard against mere symbolic support for religious freedom to ensure this right is secure for everyone, everywhere.

To see other pieces in this series visit: Cornerstone Forum: Translating Diplomatic Engagement to On-the-Ground Improvements in Religious Freedom

Nigeria is in the eye of the storm for insecurity and persecution, where the rights of minorities — including Christians — are violated with reckless abandon. Nigeria is now a country where being a Christian is synonymous with martyrdom. Beyond the few figures reported in Western media, issues of religious freedom in the country are real and grave. The issues are complicated because of palpable fear, political correctness, lack of an agreeable response from leading Church figures and at times, fear of elimination. Beyond the physical violence, there are all kinds of discriminatory and marginalizing legal and non-legal instruments used to exclude Christians from access to power, including infringements on the right to freedom of worship. Although freedom of religion is enshrined in Section 38 subsection 1 of the 1999 Constitution, the precarious nature of being a Christian in Nigeria leaves no one in doubt that such constitutional provisions are merely on paper.

What constitutes infringement of religious freedom can be traced to pre-colonial Nigeria. First, the expansion of jihad (holy war) waged by Usman Dan Fodio against the Hausa State of Gobir from 1804 to 1808 set the stage for abuse of religious freedom in Nigeria. In that war, Dan Fodi annexed Northern Nigeria for Islam with plans to make inroads across the country. The native Hausas fell victims to this onslaught. This was met with strong resistance in the Middle Belt, the southeast, and the southern regions of the country. Tensions between Muslims and Christians across the nation—and particularly in those northern areas annexed by Fodio—have fomented ever since.

Religious Freedom in Nigeria

As a country, Nigeria includes more than 400 languages, 250 ethnicities as well as rich cultural and religious identities. As such, Section 10 of the 1999 Constitution states that Nigeria is a “secular state.” The Constitution also “prohibits both states and the Federal Government from adopting any religion as state religion; and guarantees to every person the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion as well as the right to freedom from discrimination on grounds, inter alia, of religion.”

Yet, under the fundamental objectives and directive principles of state policy, Chapter II of the Constitution enjoins the state to provide facilities for, among other things, religious life. This, in addition to the provision of Sharia penal code in the Constitution, provides a cover for the apparent superiority of one religion over others and the mindless disregard for religious liberty the nation is currently witnessing.

In his paper titled “Is Nigeria a Secular State? Law, Human Rights and Religion in Context,” Ogbu (2014) observes that: “While most Christians argue for separation of the Nigerian state from religion, most Muslims advocate the fusion of religion, the state and the law. To many of them, the Sharia ought to govern the totality of the life of a Muslim from cradle to grave.” The reality on the ground shows that there is no time in the history of Nigeria that ideological divisions have widened and weakened the common ground and the nation’s civic life like today. Observers have blamed this selective perception and treatment meted to Christians on religious superiority and policy somersaults.

Like other multi-religious countries of the world, where fruitless and futile wars are fought over attempting to supplant secular constitutions with theocracy, the deliberate action of sidelining Christians is perpetrated through physical and non-physical persecution. International Christian Concern (ICC) has identified two main sources of violence in Nigeria: namely the Boko Haram insurgency, a violent Islamist sect which has held sway in the Northeast for the past three decades and radical Fulani militants, mostly Muslims who are migrant herders spanning Sub-Saharan Africa in contestation of land with local Christian farmers in the Middle Belt region of the country.

ICC reported that no less than 896 civilians were killed in violent attacks in Nigeria during the first three months of 2022. Of particular concern is the systematic targeting of Catholic Churches as well as the abduction and killing of Catholic priests. On June 5, more than 50 Catholic parishioners were killed on Pentecost Sunday in an attack on St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church in Owo, a town in southwestern Nigeria, by suspected Fulani herdsmen. The Owo incident is similar to the 2011 Christmas suicide-bombing at St. Theresa’s Catholic Church, Madalla, in Niger State, which claimed the lives of 39 parishioners. Several other attacks on churches and parishioners were perpetrated in the last decade.

From rape to abduction and forceful conversion to Islam through marriage, Christian families in the north have suffered trauma with little success in litigations due to biased judgements in courts that are headed by Muslims.

Studies by scholars like Barkindo et al (2013) and Zenn and Pearson (2014) indicate that Christian girls are kidnapped by Boko Haram, forcefully converted to Islam and married off to commanders with impunity. In April 2014, 276 Christian female students aged between 16 and 18 — known internationally as the “Chibok Girls” — were kidnapped by Boko Haram militants from their dormitory at Government Girls’ Secondary School in Chibok, Borno State. In February 2018, 110 schoolgirls aged between 11and 19 were kidnapped by Boko Haram from Government Girls’ Science and Technical College in Dapchi, Yobe State. Leah Sharibu, who was reportedly not released because of her Christian faith, is said to have given birth to a child. She is still in captivity.

Christians have been killed by angry mobs for reportedly defaming Islam, insulting the Prophet, or blasphemy with impunity. Evangelist Eunice Elisha was killed on July 9, 2016 for preaching in Kubwa, Abuja FCT. In the same year, the wife of a Deeper Life Pastor Mrs. Bridget Agbaheme was beheaded by a mob of religious extremists who accused her of defaming the Islamic religion. In March 2021, Talle Mai Ruwa was killed and burned by irate youths in Sade, Bauchi State for allegedly insulting the Prophet of Islam.

In May 2022, Deborah Yabuku, a Nigerian female Christian student of Shehu Shagari College of Education in Sokoto, was murdered in cold blood and burned alive for blasphemy claims. In Maiduguri, police also arrested one Naomi Goni for alleged blasphemy against the Prophet of Islam. Mrs. Rhoda Jatau, a nurse, escaped death in Warji, Bauchi State in a suspected blasphemy case. A Muslim, Ahmad Usman, was recently stoned and burned alive in Abuja after being accused of blasphemy.

Researchers at Open Doors UK recorded the killing of more than 4,650 Christians in Nigeria in 2021 — making the country one of the most dangerous places for Christians. To be sure, Christian persecution in Nigeria takes the form of torture, harassment, beheading, loss of ancestral home, imprisonment, physical torture, kidnapping, threats, beating, rape and loss of family. Christians in the country suffer unwarranted killings/clashes and destruction of Churches and rectories.

But Christians are also marginalized by government policies and practices. Discrimination against Nigerian Christians through the enactment of laws, policies, and government-led initiatives — particularly in the north — indicates strong preference for the Muslim population and further restricts the full exercise of religious freedom for non-Muslims. Adherents of the Christian faith in northern Nigeria are subjugated under the Fulani Emirate System and denied freedom of worship or land acquisition for building of Churches. In a position paper presented at the Northern Governors Forum meeting held on 7 May, 2009 at the General Hassan Katsina House in Kawo, Kaduna State, the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) Northern States listed 35 ethnic minorities forced under the Fulani Emirate System and called for a change of status quo. This ill treatment is in addition to denial of equal rights to education, specifically admission into public institutions, and employment opportunities.

Some government policies are enacted to give advantage to Muslims. For example, in 2019, some Arewa youths under the aegis of Coalition of Northern Groups (CNG) gave southern leaders 30 days to accept the Rural Grazing Area (RUGA) policy intended to favor Fulani herders in peace and a 30-day ultimatum for President Buhari to implement it. After public outrage, Punch Newspaper reported that the project was suspended.

On August 7, 2020, President Buhari signed the Companies and Allied Matters Bill 2020 into law to regulate the activities of religious bodies including investigating their finances. Social commentators saw this as an affront on the Church because the law excluded Islamic institutions, which are covered by Sharia law’s penal code.

In December 2019, the Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN), Justice Ibrahim Tanko-Muhammad, advocated for the teaching of Sharia law in Nigerian universities in arabic language in his remarks at the 20th Annual Judges Conference at the Faculty of Law Moot Court, Kongo Campus of Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Kaduna State. Justice Muhammad Danjuma blamed Muslims for not being courageous enough to move Sharia law forward in Nigeria and urged them to do what is necessary to advance Sharia. On April 11, 2008, when CAN demanded to know whether Nigeria was a full member of the OIC, Minister of State Alhaji Tijani Kaura took three days to respond in the affirmative. Nigeria’s former Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Dr. Nurudeen Mohammed, also allegedly described Nigeria as an “an Islamic State with the largest Christian population” at an August 2012 OIC meeting in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. He made this statement in defiance of sections 10 and 42 of the 1999 Constitution, which stipulates that Nigeria is secular with a multi-religious population.

In a similar circumstance, Christian parents woke to attempts by the Ministry of Education to merge Christian Religious Knowledge (CRK) and Islamic Religious Knowledge (IRK) in the basic curriculum in 2017. While all students (including Christians) are forced to take Arabic and Islamic studies as a compulsory course, Muslim students do not take Christian Religious Studies (CRS) where it is taught. In fact, in over 80 percent of government-owned primary and secondary schools across northern Nigeria, there are no CRS teachers because the government does not employ them. Christians saw the merger as a ploy to enforce the teaching of Islam on Christians. After much agitation, the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC) was asked to separate the two subjects.

The Church’s Response to Religious Freedom Violations

The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Nigeria (CBCN) has issued public statements and released communiqués to condemn the perilous circumstances of Christians in the country. These communiqués are often complimented by using the pulpit to preach against marginalization of Christians in Nigeria. This moral approach is most common among Catholic priests as they engage their parishioners daily and call on the state to ensure religious freedom. The hierarchical nature of the Catholic Church places responsibility on a local Bishop or priest to speak on behalf of the Church and, where the leader is not proactive, the Church suffers for it. However, leading figures in the Catholic Church in Nigeria—including Anthony Cardinal Okogie, John Cardinal Onaiyekan, Archbishop Ignatius Kaigama, Bishop Godfrey Onah and Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah—continued to call for peace as well as draw the attention of the world to the plight of Christians in the country.

Dialogue has been an important engagement tool for Christians over the years. The Catholic Church has established a Dialogue Commission in all the Catholic Dioceses across the country. The Commissioners were charged with promoting dialogue and facilitating peace on behalf of the Catholic Church.[1] In 1996, the Catholic Diocese of Kano, for example, established the Centre for Comparative Religion to underscore the importance of dialogue in peacebuilding and peaceful coexistence. The Nigerian Inter-Religious Council (NIREC) was inaugurated in September 1999 by former President Obasanjo. It is made up of 50 members, 25 Christians and 25 Muslims and provides religious and traditional leaders with a platform to use dialogue in the promotion of peace and stability.[2] The Anglican and Methodist Church in Nigeria formed the Islam in Africa Project (IAP) in 1958. The objective of the project was to educate and motivate Christians on how to use dialogue to deepen their understanding of Islam.[3] In 1993, the Lutheran Church initiated the Association for Christian-Muslim Mutual Relations in Nigeria (ACMMRN). The thrust of its activities was centered on dialogue and engagement as a tool for awareness, respect, tolerance and peace.

However, the dynamics are different within evangelical and pentecostal churches. Since pastors own their churches and speak for themselves, the response to infractions of religious freedom is met by a reactive and, at times, retaliatory, approach.Protestants show strong support for and reliance on theChristian Association of Nigeria (CAN). Although CAN has tried to unite Christians to demand religious freedom, in the past, some leaders of the association have failed in their efforts by instead deferring to the interests of politicians. In these matters, the response of CAN has often been reactive rather than preventive. The Association most often issues statements without a robust strategy that militates against the onslaught of Christians.

Challenges to the Church’s Efforts to Advance Religious Freedom

Inconsistent International Engagement

While world leaders have condemned attacks and kidnappings of Christians across Nigeria, there is no consistent strategy to address these systemic and recurring challenges to religious freedom in the country. The U.S. Department of State designated Nigeria as a “Country of Particular Concern” due to religious freedom violations perpetrated or allowed in the country in 2020. This was the first such designation since it was first recommended to the State Department in 2009. However, the State Department removed this designation from Nigeria in 2021, despite continued religious freedom violations across the country.

Despite the Church’s broad international engagement, lack of consistent and strategic international initiatives on religious freedom concerns has relegated the issue to a matter of domestic politics.

Limited Public Engagement or Protest

Although the CBCN organized two significant protests to draw attention to the persecution of Christians in Nigeria, these protests were not sustained. Very few Christians, including members of the clergy, participated in these protests because of security concerns.

Under-Developed Reporting Processes

Cases of abductions, killings, forceful conversions, and other violations are not consistently documented and reported. Under-developed reporting processes often result in anecdotal stories without adequate documentation or factual analysis. For instance, the Catholic Secretariat of Nigeria (CSN) is yet to have a full list and profile of all the priests and religious (male and female) that have either been killed or kidnapped in various parts of the country. As a result, the government as well as international actors are not compelled to respond decisively to violations.

Lack of Unified Christian Voice on Religious Freedom Concerns

Christians in Nigeria are unable to speak with one voice on matters relating to religious freedom. This lack of cohesion among denominations significantly undermines efforts to address challenges to religious freedom in Nigeria.

Limited Legal Strategy

Although a few significant cases — like that of Ese Duru — involved legal action, the Church in Nigeria is often concerned with moralizing matters rather than resorting to legal action. Legal teams for defendants in cases, in contrast, can boast remarkable support. For example, more than 50 lawyers were in court to defend the suspected killers of Deborah Yakubu in 2022.

Essential Next Steps for the Church

The responsibility of making development partners and various stakeholders across the globe to rally support for the persecuted Church squarely lies with the leadership of the Church. The Church should take advantage of its diaspora population to get the West to invest in moral, logistical and financial support towards advancing religious freedom.

This can only be achieved if the Church speaks in sights and sounds, data and scientific facts rather than through emotion and sentiments. To this end, the national secretariat of CAN and the CSN, which is the administrative organ of the CBCN, should create a research desk that accurately and consistently documents incidents of persecution against Christians.

And while moral and prophetic actions are crucial, the Church must not shy away from engaging in legal action where it is needed. The Justice, Development and Peace Commission (JDPC) in various Arch/dioceses and provinces should take legal action whenever there are cases of forced marriage or forced conversion. Such litigation would likely draw public attention, nationally and internationally.

Christian leaders must build community capacity to combat Christian persecution through education, dialogue series in inter- and intra-faith engagements as well as other multimedia approaches. Amid complicity by the state, unless Christian leaders and the West rise to the occasion, Christians would, in the words of Rene Wadlow (2015) remain under “the long shadow of Usman Dan Fodio” for a long time.

[1] Thaddeus Umaru,2013. Christian-Muslim Dialogue in Northern Nigeria, A Socio-Political and Theological Consideration, New York: Xlibris LLC, p. 192.

[2] Nigeria Inter-Religious Council (NIREC), 2009. http://www.nirecng.org/history.html

[3] Ibid., p. 195.

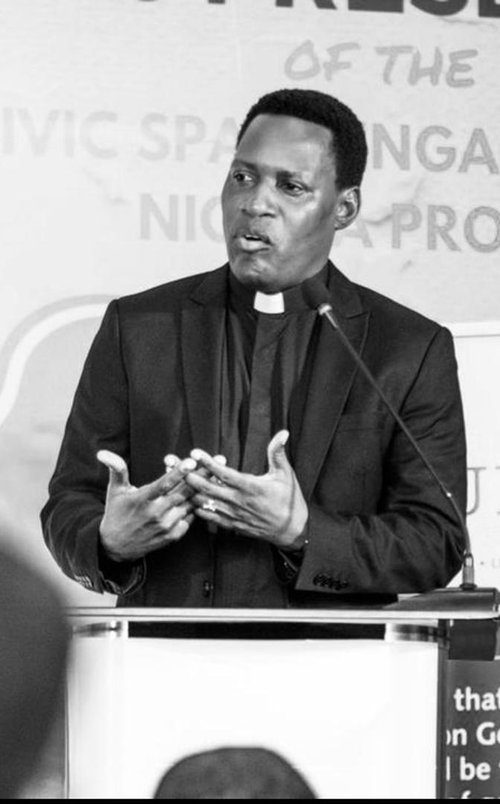

Fr. Atta Barkindo is the Director of The Kukah Centre: Faith, Leadership and Public Policy Research, Abuja-Nigeria. He is a priest of the Catholic Diocese of Yola. In August 2007, Fr. Atta proceeded to the Dar Comboni Institute for Arabic and Islamic studies, Zamalek, Egypt where he obtained his BA in Arabic and Islamic studies. In 2009, he was accepted at the Pontifical University for Arabic and Islamic studies, PISAI, Rome, Italy where he graduated with a Licentiate Degree in Political Islam and Inter-Religious Dialogue in 2011.

As recently as August 2020, Fr. Atta led a team of researchers from the United Nations Development Programme Borderlands Centre, Nairobi, Kenya to provide up to date actor mapping of the activities of Boko Haram factions around the Lake Chad Basin. In October 2020, Fr. Atta was selected by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) to develop a roadmap on transitional justice in Nigeria. He is also Research Fellow for Open Doors International, Netherlands, the World Watch Monitor, UK and Global Initiative on Civil Society and Conflict, University of South Florida. Fr. Atta is also a member of the Board of Trustees (BoT), Africa Research Institute, London. Fr. Atta has authored books, technical reports and policy documents, one of which is “Boko Haram’s Exploitation of History and Memory.”

In January 2018, he was appointed the Executive Director of The Kukah Centre, and in August of the same year, he was made the Head of Secretariat of the National Peace Committee. He directly works with General Abdulsalami A. Abubakar and Most Rev. Dr. Matthew Hassan Kukah, Chairman and Convener of the Peace Committee respectively, to facilitate peaceful elections and transition in Nigeria.

Fr. Justine John Dyikuk is a Lecturer of Mass Communication, University of Jos, Nigeria where he is involved in teaching, research and community service. He holds a Diploma and Master of Arts Degree in Pastoral/Communication Studies from Catholic Institute of West Africa, Port Harcourt (2012 -2013) and University of Calabar, Nigeria (2013-2015). He bagged two Bachelors’ Degree in Philosophy and Theology from the Pontifical Urbaniana University, Rome (2000-2003) and the University of Jos (2004-2008). He has contributed over 50 articles in both local and international peer-reviewed journals with 3 books to his credit. His research areas include political communication, media and society, and investigative reporting. He is the editor of Bauchi Caritas and Director of Communications for Bauchi Diocese.

Fr. Dyikuk works with the youth as Chaplain for Young Catholic Students (YCS) of Jos Province which covers the Archdiocese of Jos and Bauchi, Pankshin, Shendam, Jalingo, Yola and Maiduguri Dioceses. His articles have appeared in Nigeria’;s leading investigative online newspaper Premium Times, Union of Catholic Asian News, La Croix International, US- based Crisis Magazine and other diocesan newspapers. The accomplished journalist is the convener of Media Team Network Initiative (MTNI), a faith-based Not-for-Profit Organisation which prioritizes mass literacy and entrenching peaceful co-existence across Nigeria. He is engaged with The Kukah Centre, Abuja as a trainer, researcher and facilitator. He was ordained a Catholic priest for Bauchi Diocese on 13 June, 2009. He is currently the Dean of Wuntin Dada Deanery and a Consultor in the Diocese.

THE RFI BLOG

Is Egypt’s Government Trying To Take Over Christianity’s Most Important Monastery?

Does Southeast Asia Lead the World in Human Flourishing?

RFI Leads Training Session on Religious Freedom Law and Policy for U.S. Army War College

Oral Argument in Charter School Case Highlights Unconstitutional Motives Behind OK Attorney General’s Establishment Clause Claim

Largest Longitudinal Study of Human Flourishing Ever Shows Religion’s Importance

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Reaffirming Religious Freedom: Bridging U.S. Advocacy and Iraq’s Constitutional Framework

Political Polarization, Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty

Bridging the Gap Between International Efforts and Local Realities: Advancing Religious Freedom in the MENA Region

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action