This article is published under RFI’s Freedom of Religious Institutions in Society (FORIS) Project. FORIS is a three-year initiative funded by the John Templeton Foundation to clarify the meaning and scope of institutional religious freedom, examine how it is faring globally, and explore why it is worthy of public concern.

Somewhere along the way America lost focus on the rehabilitative ideals of its earliest prisons. While never intended to be comfortable, the original ambition of incarceration was not simply to be punitive, but also to be “correctional” — to leave prisoners better off than we found them, for the good of inmates and the country. Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail (1773 – 1838), America’s first overtly “correctional” regime, experimented with opportunities for self-betterment including a school for carpentry, fair wages for shoe making and stone cutting, family visitation, visitor-led religious services, and early release for good behavior. The goal was to prepare citizens for the new mercantile economy, not to keep them relentlessly warehoused. Early models of correctional practice were more collaborative than prisons of today, combining state resources with philanthropic, religious, and civic assets to better manage offenders. The main goal was to incentivize future good behaviors, not simply punish former bad ones. But in a legacy that has defined the entire history of corrections, Walnut Street Jail soon became a nondescript human dumping ground – so overcrowded and rampant with violence and disease that betterment of prisoners was abandoned.

Today’s prisons feature severe overcrowding, widespread mental illness, high levels of post traumatic stress disorder, almost nonexistent levels of programming, extreme violence, unforgiving sentences, corrosive employee turnover, and costly recidivism.

National data reveal that the longer someone spends in prison, the more likely they are to reoffend. Because of these toxic burdens, coupled with shrinking resources, today’s prisons not only fail to “correct,” they often make things worse. And at great expense to taxpayers.

But a new model of corrections is quietly taking hold in the United States, built in part on the ideals of old, but also putting into place newer practices gleaned from the painful experience of warehousing inmates. By necessity, these new approaches are being developed in some of America’s largest maximum-security prisons, and yet largely remain hidden in plain sight. However, in order to fully appreciate the accomplishments of these innovations, it will require an openness to rethink many current practices both inside and outside of prisons.

“A HOPELESS PLACE:” PARCHMAN FARM

Perhaps no better example of the multi-dimensional failure of America’s prison system exists than Mississippi State Penitentiary — the former plantation known as Parchman Farm, America’s second-largest maximum security prison. As an institution where “no one is safe, not even the guards,” Parchman was struggling to retain staff, while staving off federal intervention, even before COVID-19. After losing nearly half its correctional officers, Mississippi Department of Corrections has also lost roughly one third of its education staff and 20% of its probation officers. Numerous beatings, rapes, and literal burnings of inmates have been documented recently in Mississippi state prisons.

Sentencing reform legislation aimed at lessening overcrowding while diverting savings to rehabilitation was briefly successful — only to have these monies clawed back by the legislature to help pay for corporate tax cuts. Meanwhile, Mississippi’s inmate population has crept back up to near record levels.

But Mississippi is by no means unique. The starvation diet imposed upon many state prison systems is part of a longstanding funding crisis faced by corrections overall, dramatically impacting prison operations. In Florida’s prison system, for example (the nation’s third-largest), only 6% of inmates receive any type of programming. Florida’s current Secretary of Corrections describes Florida’s system as in a “death spiral,” while chair of the state senate’s criminal justice appropriations committee noted: “This is not a prison system that anybody can look you in the eye and tell you a person … will be safe in the state’s care.”

GOD HELP US: NEW PARTNERS IN CORRECTIONS

News that retired warden Burl Cain of Louisiana State Penitentiary (LSP) at Angola had been confirmed as Secretary of Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDC) came as good news to our ears. Southern plantation prisons play a unique role in American corrections and they face unique challenges. Mississippi State Penitentiary, the state’s largest prison, is second only to Angola in size. Recent accounts show Parchman’s physical plant to be decrepit, septic, unheated, and dangerous. Conditions have deteriorated to the point where inmates openly attack staff for the purpose of being sent to solitary confinement. Such conditions comprise what Cambridge University prisons scholar Alison Liebling calls “failed state” prisons. In “failed state” prisons, even the most basic level of care and safety cannot be provided by authorities. Such institutions cause more disorder than they prevent. Steeped in dynamics of race relations that date to America’s founding, Angola and Parchman are America’s largest and most notorious plantation prisons. The large majority of inmates in both institutions have always been black.

On a team of five criminologists, we spent five years at Angola evaluating the impact of the

prison’s unique Christian seminary, established in 1995 after Congress revoked Pell Grant eligibility for convicted felons as part of the 1994 Crime Bill. Fearing an increase in violence and facing continuous budget cuts, then Warden Burl Cain described himself as desperate for his job. Through friends at church he reached out to New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary (NOBTS) to inquire about the school offering a few courses as a gift to the prison. As Cain hopefully put it, he wanted NOBTS faculty to come “on campus” at Angola.

As described in Chapter 2, during LSP’s own federal takeover of 1974, religious practice was identified by inmates as one of the few program options prisoners actually valued, thereafter requesting permission to turn what they described as informal “religious clubs” into prison-approved programs. Inmates had long gathered on Angola’s yards to sing Gospel music and preserve a semblance of community. With the state’s permission, inmates were allowed to form their own Baptist, Pentecostal, Catholic, Methodist, Episcopal and other worship communities as new programs of the prison.

Several inmate-built interdenominational chapels and two Catholic churches exist on the grounds of Angola today. A small population of Muslim inmates also openly worships at the prison.

After initial reluctance, NOBTS faculty surprisingly decided that instruction at Angola not only fell within their mission–it affirmed their mission. Moved by the isolation of Angola and its active religious life, NOBTS Dean Dr. Jimmy Dukes described encountering inmates “in threadbare clothing articulating themselves about King David’s moral failings or comparing the violence of illicit drug markets to that found in 1 Kings.” No pushover, Dukes stayed cool to the overtures of inmates. But Dukes soon learned by attending services and walking the prison –that few ever actually left Angola alive. 90% in fact died on site, with many quietly buried in the prison cemetery after a life sentence with no family members present.

As Dukes absorbed the desolation of Angola, he concluded there was literally no earthly gain to inmates’ moral curiosity about the Bible. Dukes also confesses to altering his own viewpoint regarding what he now considers “throw-away prisons.” At the conclusion of these early visits, he and others felt something was not right–and that something should be done. In its decision to plant a fully functioning Christian seminary on the grounds of Angola, NOBTS single-handedly salvaged collegiate education for convicted felons at a time when virtually no other prison was able to do so.

Once established, the seminary immediately opened enrollment to inmates from across Angola’s five prison complexes. The school hired an outside Director to work full time on campus at Angola and four years later graduated its first small cohort of what they called “trained ministers.” In addition to bringing collegiate education back to the prison, NOBTS accomplished something more novel: they had pierced the hermetically-sealed environment of America’s largest maximum-security prison. By introducing a host of outside stakeholders with a newly-vested interest in positively impacting the prison, the inmates found their environment unalterably changed.

A NATIONWIDE MODEL: NEW STAKEHOLDERS, NEW VIEWPOINTS

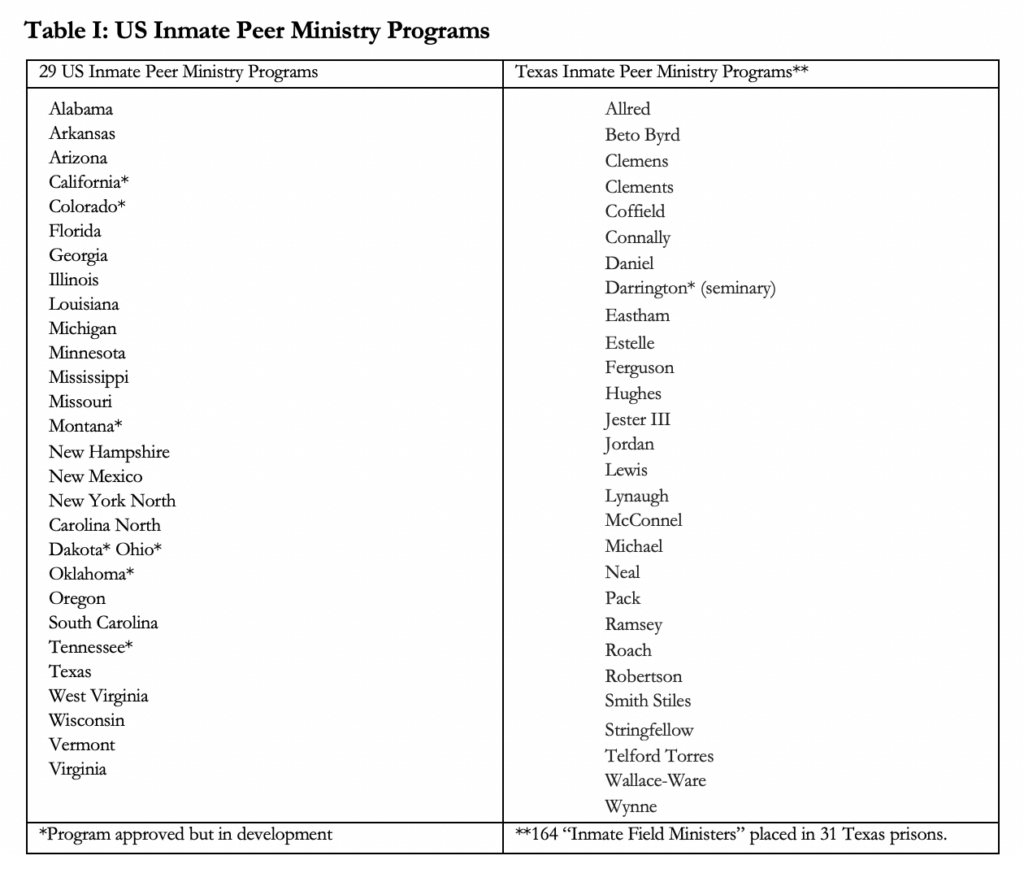

In what is fast-becoming a nationwide model in public-private partnerships, prison wardens all over the United States are now collaborating with religious educators and non-profit organizations working inside over 50 US maximum-security prisons in 29 states. Paid for with private external funding and endorsed by powerful legislative advocates, a prison reform movement not dissimilar to that initiated by the Religious Society of Friends is now underway in the United States. Motivated by concerns about prison conditions and America’s failing prisons, religious volunteers are stepping up to deliver a new “purpose-driven” ministry. Just before the onset of COVID-19, religious educators were dramatically expanding their presence in many dozens of US maximum-security prisons.

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IMPROVING PRISONS: HOW IT WORKS

Because space limitations constrained worship on Sunday mornings at Angola, religious services were scheduled each weekday evening–with many inmates thereafter attending open services 7 days per week. With this denominational cross-fertilization, Angola’s congregations congealed around a shared sense of purpose, collectively “tithing” to indigent prisoners with gifts including everything from soap, toothpaste and socks, to spare sweatshirts. Put another way, after a season of prolonged violence and prison neglect, Angola’s inmate churches became organizing venues not just for religious programming, but for all kinds of enrichment programs including remedial education, 12-step meetings, individual outreach to the cell blocks, and workshops of all kinds.

Since religious leaders must be confirmed by the faithful, Angola’s churches bolstered inmate voice and leadership through nominating their own “pastors.” Priding itself on the functional equivalence of their “prison seminary” to any on the outside, Angola also began to attract free world attention. Evangelists and preachers soon visited Angola’s churches by invitation–opening a vibrant new channel of philanthropy to the prison.

Visitors brought precious items in short supply: boxes of winter clothing, personal hygiene items, socks, blankets, work boots, stationery and postage, and reading materials. In organizing to distribute these goods, Angola’s inmate churches suddenly took on a unique caretaking role for the entire prison. A sense of community developed, with inmates organizing a service in response to the tragic death of a correctional officer’s young child and frequently sharing food and worship with staff. While no panacea to the many challenges of life in a maximum security prison, the Angola prison seminary bolstered the prison with outside resources at a time when governmental support for inmates waned.

With most correctional officers holding only a high school diploma or less, Inmate Ministers soon found themselves to be among the most educated individuals on site.

Trained in process counseling and conflict management, and having unique access to fellow inmates, new seminary grads immediately found their greatest workload not in prison chapels but in dorms and cell blocks. Security warden Davy Kellone witnessed seminary students consoling an inmate in distress. In crisis situations, after a suicide or upon notification of the death of a loved one at home, “the seminary students were far more effective than sending over a chaplain or security,” Kellone stated. “There’s an access level there that I don’t have–because it’s those men helping each other as equals.” Starting in 1999, Kellone implemented Angola’s unique “Inmate Minister” program–sending seminary grads across the prison to “check on inmates and just talk to them. That’s it. Nothing disciplinary.”

Together Cain, Kellone and head chaplain Robert Toney placed seminary graduates with trustee status in the role “offender minister,” assigning formal caseloads in dorms and cell blocks for counseling and wellness checks. Said Cain: “Their only job is to try to make sure people are ok and see what they need. That’s it. No interrogation. If we can give them what they need, we will. If they want to be mean, we can do that too. It’s like Burger King: have it your way.”

Multiple independent data sources show violence and self-harm at Angola fell for 20 straight years after implementation of the prison seminary. While not the only program active at the prison, both staff and inmates independently stress the importance of Angola’s unique religious culture as the central organizing venue for community life.

Cain explains he took chances on inmates because he didn’t have a choice–and that occasionally he got burned. But to his surprise, most of the time he did not. This proved most transformational for Cain himself: he’d asked for inmates’ help and received it.

Angola’s administrative security staff first resisted Cain’s decision to allow Inmate Ministers free movement across the prison. But amid continuous budget cuts and few program options, Cain pressed forward. The old model was failing. “The only time we ever have enough money to run this prison safely is after we lose a lawsuit. It’s no way to live.” Angola’s seminary grads were now doing work once reserved for prison chaplains and professional counselors–and seemingly doing a better job of it. Violence and self-harm continued to fall. Cain realized the culture that had to change was not just the inmate culture–it was his own culture, that of “so-called professional corrections.”

THE A-TEAM: “ONLY THEY HAVE THE REAL CREDENTIALS”

Parchman Head Chaplain Ron Olivier graduated from Angola’s prison seminary in 2005. Paroled in 2018 and subsequently recruited by now Commissioner Burl Cain to work as Head Chaplain at Parchman, Olivier pastored an inmate church at Angola’s Camp C for 15 years. A remote out camp of the prison challenged by few resources and even fewer visitors, Camp C often became a desperate place. In order to hire Olivier, Cain boldly changed the rules to allow convicted felons to work in the prison. “But who better?” Cain asks. “These men have literally saved people’s lives. This is the A-team.”

Just as former drug addicts make the best addictions counselors, Angola’s former Inmate Ministers possess what Cain calls “the real credentials” –actual lived experience in successfully facing the challenges of prison. Inmate Ministers were model inmates by definition, earning trustee status as a condition of application–and then rising to the top of a competitive application process. The most important credential of Cain’s A-Team is successfully facing incarceration with a long sentence. And such experience is increasingly recognized by correctional authorities as a valuable resource. As Texas Department of Criminal Justice Executive Director Brian Collier recently stated, speaking at a recent Texas prison seminary graduation ceremony at Darrington Unit Correctional Institution:

“I don’t have it, our chaplains don’t have it, a lot of our volunteers don’t have it. You’ve got credibility with your peers in the system, and that’s what matters.

You’ve walked in their shoes, you’ve been where they are, you know that path, and you’ve seen a different path. As you walk that path, I want you to hear this from me directly: I absolutely fully support your mission. At TDCJ we fully support what you’re doing, our wardens fully support what you’re doing, and we are on the same team. We’re excited about the changes that your work is going to bring.”

In a growing number of prisons all across the United States, religious educators are partnering with correctional leaders in delivering tuition-free religious education programs to carefully-selected inm

ates-who are then put to work in maximum-security facilities. Sponsored by evangelical volunteers concerned about prison conditions and often motivated by their own experiences volunteering inside, privately-sponsored religious degree programs for inmates in US prisons are expanding rapidly. Just prior to the onset of COVID-19, such programs were active in 29 states and over 50 US maximum-security prisons. While having faded from view since the heyday of President George W. Bush’s “faith-based initiative,” prison administrators have continued to adopt resources from religious sponsors for everything from instructional materials to actual program delivery inside prisons. In numerous instances since the mid-1990s, sustained austerity and high staff turnover has resulted in prison wardens turning to religious volunteers of all kinds.

WOUNDED HEALERS IN “FAILED STATE” PRISONS

“When our wounds cease to be a source of shame, and become a source of healing, we have become wounded healers.” — Henri Nouwen

In recruiting released Angola seminary grads as staff chaplains for Parchman, new Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Burl Cain is drawing on experience from his worst days at Angola. Cain references “Angola’s bad old days” as a key resource for Parchman. “They’re just here to instill some hope and help build a sense of community, if they can.” NOBTS now has a functional seminary at Parchman modeled off Angola’s and donations from outside churches have already begun helping the prison. Pending concerns regarding COVID-19, a new inmate chapel–currently under construction–is slated to open at Parchman on Easter Sunday, 2021.

Undaunted by the violence and conditions at Parchman, A-team members remain hopeful. “See, everybody sees Parchman right now probably differently than we see it,” explains former Angola church leader and new Prison Chaplain Sydney Deloch:

“We’re not as challenged by the environment as an outsider would be. See this is kind of like home for us. It’s normal for us. But what we’ve got here now assembled is a strong team of leaders to let men in this prison know what we already know: that it can get better. I did 41 years at Angola. I think you’ll agree that’s hard time. Our mission is to bring back respect and love to this place, a hopeless place. I was saved in prison – you understand? There’s no going back from that. All of us came out of this very same hog pen, you get it? So I’m here to say to each and every man you are still a man. And I’m going to treat you like a man. Like a human being – first by exhibiting kindness but then by listening.

Nothing they tell me is going to make me flinch. I’m back in prison because I love God and I’m a witness. And it’s simple -if you put love at the center of your life you will be free no matter where you are. No enemies. No agendas. Just God’s love. So see I left prison a long time ago, even when I was still incarcerated. And that’s why I’m here. You get it? That’s why we’re all here. To tell these men what we already know.”

Academic critics of religious immersion programs in prison argue they reinforce hierarchies of economic and race relations that violate inmates’ Constitutional rights, while ignoring larger conditions regarding race and social inequality. Religion in prison helps the state paper over the sinfulness of social conditions that cause mass incarceration, they argue, tautologically scapegoating blame for crime on the “sinners” in prison. Preaching to a captive audience in this way is illegitimate, they say, and both ignores and reproduces the power imbalances that cause so much crime in the first place. Religion as co-opted by state authorities, they argue, helps mask the very social injustices that drive mass incarceration.

But these concerns are not lost upon inmates themselves–and to suggest otherwise is mostly academic conceit by people who’ve spent very little time inside American prisons. Put simply, we did not find religion playing handmaiden to racial oppression at Angola. To the contrary. Amid the highly racialized punishment regime existing in America’s most punitive state (Louisiana), we found religion at Angola playing the role we hoped it would play: that of healing the wounded, of caretaking for the poor, and uplifting the down in spirit. We found religion at Angola enhanced inmate wellness and assisted in the reduction of violence and self-harm, especially by offering unique personalist attention to inmates’ needs and private pains—often expressed for the very first time to Inmate Ministers working with peers as they deal with difficult emotions and struggles. In short, religion in prison is stepping in where the state has failed.

Given that austerity-driven realities of state budget cuts are likely to continue amid the aftermath of COVID-19, volunteer-based resources will become all the more important for state prisons and prisoners in the years ahead. And equipping inmates to care for themselves is proving to be a uniquely powerful resource. “Will this solve all our problems? No.” says Cain. “Is it for every prison? No. For every inmate? No. But can these programs improve the lives of many men in our care while bringing us resources we desperately need but do not currently have? Absolutely.”

All facets of peer-based prison ministry and religious life described here are voluntary and privately funded. No taxpayer money is used to sustain these programs and students may withdraw at any time. Ecumenical openness characterizes religious worship in prison, for simple lack of an alternative. As former Angola inmate and current Parchman Chaplain George King puts it: “Most people think using the Bible means quoting scriptures or preaching sermons. But I think the greatest effect about using the Bible in prison is with your own life. A message is preached every day–whether we’re behind the pulpit or not. It’s about how you treat people.” As Chaplain Deloch explains: “We’re not denominational in here. We have no time for that foolishness. I’m not going to be arguing about Baptist this and Methodist that or this and that and the other. Why? Because God is not coming back for a denomination, He’s coming back for a holy nation.”

Dr. Byron Johnson serves as Senior Fellow at the Religious Freedom Institute and a Distinguished Professor of the Social Sciences at Baylor University. He is the founding director of the Baylor Institute for Studies of Religion (ISR) as well as director of the Program on Prosocial Behavior. Professor Johnson is a leading authority on the scientific study of religion, the efficacy of faith-based organizations, and criminal justice. His most recent publications have examined the impact of faith-based programs on recidivism reduction and prisoner reentry.

Dr. Michael Hallett is a full Professor of Criminology & Criminal Justice at the University of North Florida. Most recently, Dr. Hallett led a three-year study at America’s largest maximum-security prison, Angola (aka Louisiana State Penitentiary) exploring the religious lives of long-term inmates. He also serves as a Senior Research Fellow at Baylor University’s ISR.

Dr. Sung Joon Jang is Research Professor of Criminology and co-director of the Program on Prosocial Behavior within Baylor University’s ISR. Before joining Baylor University, Jang held appointments at Ohio State University and Louisiana State University. His research focuses on the effects of religion and spirituality as well as family, school, and peers on crime and delinquency.

All views and opinions presented in this essay are solely those of the author and publication on Cornerstone does not represent an endorsement or agreement from the Religious Freedom Institute or its leadership.

THE RFI BLOG

Is Egypt’s Government Trying To Take Over Christianity’s Most Important Monastery?

Does Southeast Asia Lead the World in Human Flourishing?

RFI Leads Training Session on Religious Freedom Law and Policy for U.S. Army War College

Oral Argument in Charter School Case Highlights Unconstitutional Motives Behind OK Attorney General’s Establishment Clause Claim

Largest Longitudinal Study of Human Flourishing Ever Shows Religion’s Importance

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Reaffirming Religious Freedom: Bridging U.S. Advocacy and Iraq’s Constitutional Framework

Political Polarization, Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty

Bridging the Gap Between International Efforts and Local Realities: Advancing Religious Freedom in the MENA Region

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action