Recent government actions (including an Austrian law restricting German translations of the Qur’an, a German circumcision ban, a French headscarf ban, and a Swiss aminaret ban) are restricting Muslims’ religious freedom in western Europe. Please join us on Cornerstone as diverse commentators explore the obstacles that European Muslim communities face and what these challenges mean for the future of religious freedom.

By: Timur Kuran

Suppressing a community’s religious freedoms conveys the message that its beliefs and practices are foreign, illegitimate, and unwelcome. Indeed, stigmatization is often the underlying intent. European policy makers who ban minarets generally aim to discourage Muslims from moving in and to make settled Muslims move away. Whatever the magnitude of the intended effects, the Muslim share of Europe’s population will probably keep growing for decades. The aging of European nations, high birth rates in the Middle East and South Asia, and massive governance failures in various Muslim societies almost guarantees a steady flow of new immigrants. If for no other reason, the economic and political effects of anti-Muslim policies in Europe deserve attention. Clues about the direct effects exist in past cases of religious discrimination, European as well as Middle Eastern. But these must be interpreted in the light of modern technological advances.

An immediate economic effect of the stigmatization of European Muslims is the restriction of their social contacts and employment opportunities. Anti-Muslim policies legitimize discrimination in housing and hiring. They make it socially acceptable to exclude Muslims from economically valuable social networks. In segregating Muslims socially, they deprive them of professional contacts available to other Europeans. They thus compound disadvantages rooted in poverty, poor education, and cultural differences.

The foregoing immediate effects receive abundant attention in commentaries focused on the economic conditions of European Muslims. Usually overlooked are the unintended long-run effects, which need not be unfavorable. For one thing, socially handicapped groups must work harder to succeed and cultivate special skills. For another, they may specialize in sectors that become more lucrative over time. Second- and third-generation Turkish-Germans are achieving prominence in certain expanding economic niches. These include sectors where novelty commands a premium, such as high cuisine, travel, and entertainment. They also include commerce with Turkey, whose expanding markets provide a comparative advantage to Turkish-speakers. Enterprising Turkish-Germans are also making inroads into mainstream occupations.

Two historical examples will illustrate what the future might hold economically for European Muslims in general. In medieval Europe, the usury ban on Christians relegated finance largely to Jews, a community that faced various forms of economic discrimination. The financial skills that Jews honed and transmitted across generations became increasingly valuable in the course of the economic modernization process. Skills that they acquired of necessity, because of discrimination, gave them economic advantages as the economy evolved.

The second example comes from Islam’s heartland, the Middle East. Up to modern times, states governed under Islamic law denied Christians and Jews various social, political, economic, and religious rights enjoyed by Muslims. Under the circumstances, non-Muslim minorities had incentives to seek special protections from outsiders. That made them especially open to the West’s advances. The legal protections that the Middle East’s Christians and Jews received from the West accounts substantially for their remarkable economic advances in the course of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The economic handicaps of non-Muslims thus turned into economic advantages.

The trajectory of the Middle East’s non-Muslims suggests that Muslim Europeans, insofar as their opportunities are blocked in Europe, have greater incentives than native Europeans to pursue global opportunities for enrichment. The case of European Jewry indicates that discrimination against the descendants may yield unintended benefits to today’s European Muslims.

Technological developments of the past few decades, and the resulting global economic integration, favor a reversal of fortune for currently handicapped European Muslims. They offer today’s disadvantaged minorities economic opportunities unavailable to those of pre-modern times. The capacity to prosper by serving other societies, whether through conventional trade or e-commerce, has grown by orders of magnitude through the ongoing revolution in communications. Moreover, the markets of the Islamic world, including those where Arab-Europeans have a comparative advantage, offer massive investment opportunities. Hence, the economic handicaps that European Muslims suffer directly because of religious discrimination are not insurmountable.

The political consequences of the religious discrimination in question are both more serious and longer lasting. Relative to socially accepted communities, those that are stigmatized through special restrictions develop weaker ties to the wider society. Living in perpetual tension with politically dominant groups, inevitably they develop resentments. Feelings of alienation and hostility are all the more pronounced among young adults, who are particularly prone to radicalization. In search of meaning in their lives, and a sense of accomplishment, some will be drawn to violence.

Pre-modern communities enduring religious discrimination were able to suppress the rebellious instincts of their young. As a case in point, prior to the nineteenth century Christian and Jewish communities living under Muslim-governed regimes policed themselves to keep their resentments from fueling active resistance to the state. For fear that unrest might provoke retaliation, they trained their young to accept their place in society. Hence, in spite of the discrimination they endured, by and large the Middle East’s non-Muslims remained submissive as long as the state remained strong.

Massive advances in communications have essentially eliminated the self-policing option. No longer can a community insulate its young from outside sources of influence. Muslim-European youths are now in contact with other resentful Muslims around the world. They know that their coreligionists are in arms elsewhere. Some are inevitably tempted into acting on their resentments in milieus where they will find safety in numbers. The fact that hundreds of Europeans have joined jihadi militia in Syria, Iraq, and Somalia illustrates the possibilities.

The radicalization of Muslim youths brings harm, of course, to Europe as a whole. Making all Europeans feel less secure, it aggravates anti-Muslim feelings and leads to higher spending on policing. It thus exacerbates the very social tensions that feed Muslim resentments. Reviving historical hostilities between Islam and what was once called Christendom, it fuels global tensions that may take generations to overcome.

By no means are European policies that curtail Muslim religious freedoms the sole, even the main source of either Muslim economic underperformance or Muslim radicalization. But these policies do not solve any key problem of the present. On the contrary, they deepen fault lines and heighten tensions.

Timur Kuran is professor of Economics and Political Science and Gorter Family Professor in Islamic Studies at Duke University, as well as an associate scholar with the Religious Freedom Project.

This piece was originally authored on December 17, 2014 for the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion,

Peace, and World Affairs.

THE RFI BLOG

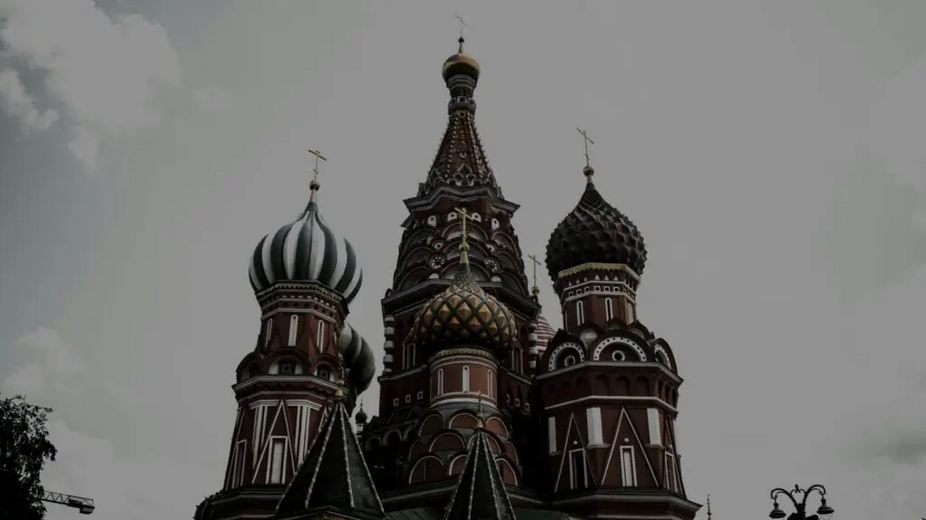

Religion, the ‘Russian World,’ and the War Against Ukraine

Religious Freedom Is Back on the UK’s Agenda

Be More Faithful, Become More Resilient: An Invitation to Religious Institutions

How Soccer Reveals Different Meanings Of ‘Secular’ In France And The US

RFI’s Ismail Royer Meets with Delegation from India

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Public Bioethics & the Failure of Expressive Individualism

Religious Liberty in American Higher Education

Scotland’s Kate Forbes and the March of Secularism

70 Years of Religious Freedom in Sweden: Prospects and Challenges