The internet promises both greater freedom and greater repression. It gives a chance of increased expression to millions of people whose views and voices have been and could still be silenced by politically repressive regimes or monopolistic media. But, it can also give those same repressive governments and media empires control so that they can erase contrary views.

Recent events suggest that currently the push for greater control is winning, sometimes abetted by major tech companies.

While China is developing a total surveillance system to monitor all of its citizens, including and especially Uighur Muslims, Muslim-majority Indonesia seems to be leading the way in establishing a specifically religious surveillance system. It is also unusual in that it is trying to enlist its citizenry in its spying system.

Indonesia’s turn to democracy, beginning with the fall of Suharto in 1998, has been accompanied by a strengthening of religiously extreme groups and a concomitant growth in the number of people accused of blasphemy. The most famous case is that of Ahok, the former Governor of Jakarta, due to be released this month after serving most of a two-year sentence, but cases are proliferating.

On August 21, 2018, Meiliana, a 44-year-old ethnic-Chinese, Buddhist woman was sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment for blasphemy. Her “crime” was that, in 2016, she had asked her neighborhood mosque in Medan to lower its sound system because it was too loud and hurt her ears. Despite declarations by Indonesia’s Vice-President, Jusuf Kalla, that mosques should indeed avoid excessive noise that disturbed others, and assertions by Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s and the world’s, largest Muslim organization, that asking for the volume of loudspeakers to be lowered could never be considered blasphemy, she was convicted.

On October 22, 2018, in Garut, West Java, members of the Barisan Ansor Serbaguna (Banser), the youth movement of Nahdlatul Ulama, apparently seized from a demonstrator and burned what may have been a flag of the pro-Caliphate organization Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI). HTI is in fact banned in the country, which means it is probably illegal to display its flag. HTI’s emblem contains the Shahada, the Muslim confession of faith, so burning it could be seen as burning a sacred text. Islamic hardliners speedily demanded that the flag burners be tried for blasphemy. Police arrested two of them, together with the man who allegedly raised the flag. The two Banser members were subsequently given the comparatively mild prison sentence of 10 days.

Grace Natalie, like Ahok an ethnic-Chinese Protestant, is a founder of the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI), which is aiming its appeal at millennials. On November 11, 2018, she addressed party members, along with their distinguished guest, Indonesian President John Widodo (Jokowi), and said that her party would not support discriminatory local laws based on “the Bible or sharia,” declaring that: “The implementation of religion-based bylaws victimize women and I have become a victim as well for criticizing such regulations.”

Subsequently, Eggi Sudjana, a politician from the National Mandate Party, which supports Jokowi’s electoral opponent, Prabowo Subianto, accused her of going against the Quran, and perhaps blaspheming. On November 22, she was questioned by police for seven hours about these accusations So far, she has not been charged.

These events, which might otherwise have passed without incident, have become inflamed because some opposition politicians and supporters have used them to foment identity politics in order to secure an advantage in Indonesia’s Presidential and legislative elections, due in April.

But, more worrying in the long term is the move by some of Indonesia’s prosecutors to facilitate the hounding of those whose religious views it holds to be unorthodox.

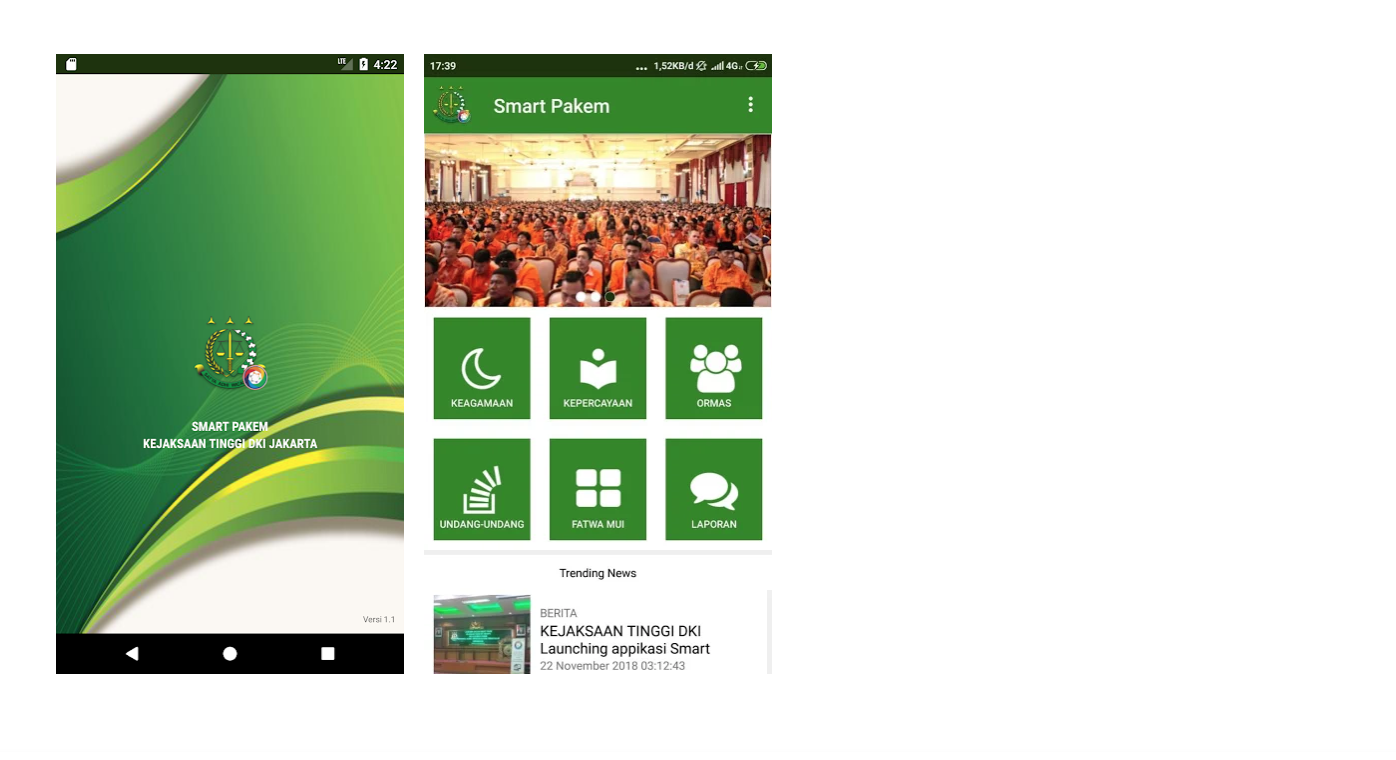

Screenshot of the Smart Pekam app available for download in the Google Play store.

On November 25, 2018, Bakor Pakem, part of the Jakarta Prosecutors office (Kejati), a body within the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) charged with religious oversight and enforcing the 1965 blasphemy law, launched an Android app that allows mobile phone users to report any individuals suspected of “religious heresy.”

The app was made available on Google Play and includes a list of purported forbidden beliefs and banned mass organizations, a directory of fatwas issued by the semi-official Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), and a form to report complaints or information about religious beliefs or sects.

It also lists Ahmadiyya, Shia Muslims, as well as the home-grown Gafatar as deviant religious beliefs, and names their leaders and gives their Indonesian office addresses.

The app was quickly criticized by human rights groups such as SETARA and Human Rights Watch. Commissioner Choirul Anam of the official National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) said the app could potentially lead to the violation of religious freedom and that the AGO’s role in overseeing religious beliefs should be abolished.

On December 28 and 29, 2018, several major Indonesian religious, cultural and interfaith leaders proclaimed a document called the Jakarta Treatise that criticized the app and, more generally, the rising tide of religious radicalism sweeping the country. Among the signers were former Constitutional Court chief justice Mahfud MD (sic), noted Catholic priest and philosopher Franz Magnis Suseno, Savic Ali from Nahdlatul Ulama, the Liberal Islam Network (JIL) coordinator Ulil Abshar Abdalla, and activist Alissa Wahid.

The Treatise also urged the government to revise the blasphemy law, and was submitted to Religious Affairs Minister Lukman Hakim Saifuddin. Minister Lukman released an official response on December 29, largely agreeing with the points in the document. He also agreed that “ultra-conservatism,” in the form of religious exclusivism and extremism, contradicted religious values.

Despite this widespread criticism, including from within government, the AGO has not backtracked on its app, not has Google withdrawn it.

Google is not on the only internet giant complicit or potentially complicit in facilitating political and religious repression. Saudi Arabia has recently managed to persuade Netflix to remove a satirical comedy show critical of its regime.

Vietnam has introduced a new cybersecurity law, which criminalizes criticizing the government online. The law, which mirrors China’s draconian internet rules, came into effect January 1, 2019, and forces internet providers to censor content at the behest of the state. The government has asked Facebook and Google to open offices in Vietnam, and to agree to comply with the new censorship and user data rules. In response, Facebook says it will protect users’ rights and safety. Hanoi claims that Google has put steps in place to open a base in the country, although Google has not confirmed this.

As of early 2019 the Indonesian app is still available on Google Play. It can be downloaded here: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=id.go.kejati_dki.smartpakemkejatidkijakarta&hl=en_GB

Google should remove it.

Paul Marshall is Wilson Professor of Religious Freedom at Baylor University, Senior Fellow of the Religious Freedom Institute and member of its South and Southeast Asia (SSEA) Team, and Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom.

THE RFI BLOG

Myths of Religious Nationalism in America and Abroad

France’s Olympic Hijab Ban Violates International Law And Exacerbates Tensions

RFI Briefs USCIRF on Lessons from 25 Years of U.S. Designating Religious Freedom Violators

Thought Police: Protecting the People from Prayer

A Religious “Delaware”: Establishing a State Haven for Religious Corporations

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action

Public Bioethics & the Failure of Expressive Individualism

Religious Liberty in American Higher Education

Scotland’s Kate Forbes and the March of Secularism