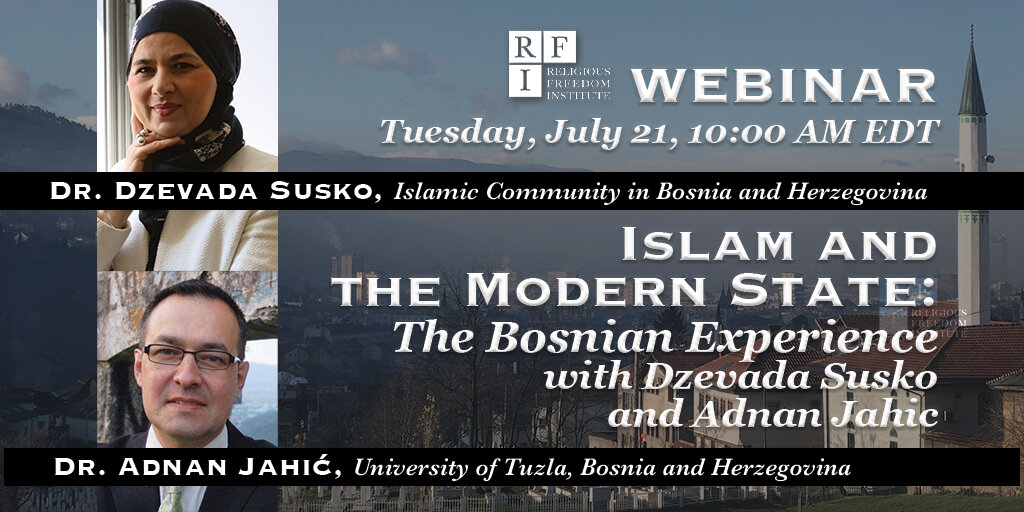

The following is a transcript from the event: Islam and the Modern State: The Bosnian Experience with Dževada Šuško and Adnan Jahić

Event Details and Speaker Biographies: https://religiousfreedominstitute.org/rfievents/webinar-nation-state-formation-and-the-muslim-majority-world-sxc8l

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0rlddn19_SE

*Transcript has been auto-generated and lightly edited for clarity though errors may still be present.

Ismail Royer: Bismillah ar-rahman ar-rahim welcome everyone. My name is Ismail Royer. I am the director of the Islam and Religious Freedom action team at the Religious Freedom Institute. I want to welcome everyone to our third webinar on Islam and the state. Today we have a real treat for you all: a very fascinating topic and very fascinating guests—an issue that is very, very rarely discussed and very little understood, and that is the experience of Bosnian Muslims with modernity, transitioning from being part of the Ottoman Empire to being annexed by other empires, and then being a part of a nation state, and all of the trials and tribulations that went along with that. I want to introduce now Jeremy Barker who is my colleague. Jeremy, why don’t you tell the audience about yourself and more about this webinar series?

Jeremy Barker: Good morning, thanks Ismail. Welcome to the series. As Ismail mentioned this is the third webinar in the series, looking at the relationship between Islam and the state. This is part of the broader work of the Religious Freedom Institute on working to secure religious freedom for everyone everywhere and exploring various dimensions to that, both the challenges and opportunities. Within this series we’ve looked at initially the concept of the nation state and then the emergence of that within the Muslim majority worlds, and then today we get to pick up a case study that brings many of those questions to bear through the Bosnian experience both historically and then up to the contemporary experience. Joining us in this conversation once again is a colleague, Osman Softic, a researcher and project coordinator based in Sarajevo, as well as professor Dževada Šuško, who is the chief of office for the diaspora community for the Islamic community in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Professor Adnan Jahić, Professor in the faculty of philosophy at the University of Tuzla. Osman, Dževada, and Adnan welcome to the conversation today. Thank you.

Ismail Royer: All right, as we were talking before we started, I discussed with you Dr. Dževada some of the things that we wanted to talk about. You mentioned that it was an encyclopedia, so hopefully you can condense that in the next 15 or 20 minutes. But first of all, of course, thank you both so much for being here. Dr. Dževada I wanted to lead off by asking you first to describe a little bit about how Islam was practiced and lived by Bosnian Muslims during the Ottoman Empire period, and then what was the experience of Bosnian Muslims when Bosnia was first occupied and then annexed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 1870s. What was the response of the Muslims there? How did they cope with that separation from the Ottoman Empire, and what was the response of the religious leadership in Bosnia, and how did they how did they cope with that transition from empire to another empire and then ultimately to the nation-state and secularization and nationalism. I know that’s a big topic but please lead us off here and maybe bring us up to somewhere around World War I, World War II.

Dževada Šuško: Good afternoon as-salamu alaykum to all of you. It’s really a great pleasure to be here. This afternoon in Sarajevo it’s four o’clock in the afternoon. Going back to the Ottoman Empire as we agreed, the Ottoman Empire ruled over Bosnia for about 450 years, so it’s a long time. At the end of the Bosnian kingdom, the Ottomans conquered southeastern Europe, including Bosnia, and installed their rule and their societal system. Then during the Ottoman period, gradually the local population converted to Islam. Mostly they gave up their medieval religion. Many scholars named it the Bosnian Church, which is which is not comparable to Christian churches, it was or something called Bogomils, some patterns so it was a heretic sect like in other parts of Europe. So Bosnia was one geographical part where this heretic sect practiced their religion. Now within the Ottoman Empire we had this system of din wa-dawla meaning that the societal political system and the religious system was one, headed by the Sultan, with the sheikh of Islam which was the religious leader of all Muslims all over the world, including Bosnia. Bosnia was the most western part of the Ottoman Empire and this geographic position was as well very important for the understanding and interpretation of Islam. A second point which is important regarding the Ottoman Empire is the Millet system, where the society was categorized according to religious identity. This is then important later with the establishment of nation states and how the people in southeastern Europe in general but as well in Bosnia and Herzegovina where the national identity is often very strongly linked to the religious identity. Now with the declining Ottoman Empire we are approaching the beginning of the 19th century. The declining Ottoman Empire in southeastern Europe with losing its strength and primarily its military strength. They introduced some reforms called the Tanzimat period to adjust the Ottoman system to the new challenges of time, but nonetheless the great powers of the 19th century gathered in Berlin at the congress of Berlin to see what is going to happen with southeastern Europe, with this power vacuum, with this “sick man of the Bosporus,” a term which is later going to be coined. The great powers then decided that over Bosnia, Austria-Hungary would rule. After a dominantly Muslim empire, a dominantly Catholic empire would rule over Bosnia. For the local Bosnian population this meant they felt abandoned, they felt disorientated, they felt kind of lost because this was the first time that they were coping with a new political system. Many questions came up. They felt that not only their religious identity was threatened, but as well their physical existence. Already in neighboring Serbia news came that Muslims were either forced to convert to Orthodox Christianity or they were expelled from their homes. Islamic architecture was gradually destroyed, but within the Berlin treaty it was decided that the Austria-Hungary would administer Bosnia and rule it militarily, whereas the Sultan, or the Ottoman Empire would still keep its sovereignty. So this was a kind of compromise for that period of time. The Berlin Congress was in summer 1878 precisely June and July, and then in April 1879 these specifics were put in detail in the Istanbul convention where for example, a kind of transitional period was allowed, whereby the Ottoman flag was allowed to be displayed for Friday prayers, Jumu’ah prayers, and on special occasions. The name of the Sultan was allowed to be mentioned during Jumu’ah prayers. Ottoman currency was also still allowed. So this gave to the Bosnian Muslim population a sort of feeling that they’re still kind of linked to the Sultan and linked to the Sheikh of Islam. For them, if you are cut off from the Sultan, if you are cut off from the Sheikh of Islam, this meant as if they had to give up their religion. Nonetheless Austria-Hungary was very smart. We have this treaty in Berlin, and this Istanbul convention, but still we have this discrepancy between what we call de facto and de jure. Legally it was set like this, but in practice Austria-Hungary expanded very quickly their sovereignty over Bosnia. This was very easily seen a couple of years later in around in 1881-1882, the conscription law was passed. In addition to the question among the Bosnian Muslims of whether it is allowed for us to live under non-Muslim rule, a new question popped up, asking the theologians of that time whether it is allowed for a Muslim to serve a non-Muslim military. So this conscripti

on law caused another migration wave. The first migration wave was when the message came that the Ottoman Empire abandoned Bosnia, and they migrated towards Ottoman lands out of fear of losing their religious identity and out of the lack of knowledge about what is going to happen. This second migration wave was launched with the conscription law. This was late 1881, beginning of 1882. Then in this same year a very important phenomenon was established in Bosnia, and this is this institution of what we today call the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina Islam the Islamska zajednica Bosne i Hercegovine, the institutionalizing of Islam in Bosnia. This was important for many reasons, but I will try to shorten it to a few points. Whereas regarding the conscription law, it is important to mention that the Sultan did not protest against the conscription law, and that this conscription law, even if it initially caused fear, on the other hand it was made so precise in terms of protecting freedom of faith or religious freedom of the Muslims who would serve the Austro-Hungarian military. Military imams were appointed, a special kitchen was opened only for the Muslim soldiers where halal food was prescribed. So the law went very much into details. Prayers were allowed, fasting was allowed, so the whole plethora of what religious freedom entails was included, including the for example exempting theology students. The sensitivity went so far that for example, families which had only one male family member were exempted so that the family would not be left alone. So this conscription law already showed to the Bosnian Muslim citizens that Austria-Hungary doesn’t have a policy of exterminating Bosnian Muslims, but rather tried to incorporate them into Austria-Hungary, or if you like into the central European concept or context. As I said it slowly became clear that as well that Austria-Hungary tried to extend its influence on Bosnia, and there was this idea to establish a separate religious institution which would care for the needs of the Muslim population. Interestingly enough the Sultan himself and the Sheikh of Islam allowed a Bosnian mufti to be appointed, meaning a religious scholar who would lead, care for, and be in charge of dealing with the religious needs in Bosnia. So the approval came then as well from Istanbul, that somebody would take care of sharia, as it says in one document, and of spiritual matters in Bosnia. But then in 1882 the religious leader whose name Reis ul-Ulema, meaning the head of religious scholars and a four-man council magistrate suleima** so which would this would say the foundation and the basis of the very first version of the Islamic Community. Later this Islamic Community would be expanded in terms of tasks and responsibilities. The approval came from Istanbul. Interestingly, another important point, and this relates to how Islam is practiced in Bosnia. Still until today we have Bosnian Muslims who, in terms of Islamic practice, they do not differ from how Turks practice Islam. We are Sunni Muslims. We belong to the Hanafi madhab, to the Matari theology. We have several Sufi orders in Bosnia which were very important for the spreading of Islam in Bosnia and in southeastern Europe in general, and we Bosnian Muslims belong to what we call the Ottoman Islamic cultural zone. For example the Bosnian language is a Slavic language, even Bosnian Muslims are Slavs ethnically. In the Bosnian language we have lots of Turkish, Arabic, and Persian words. Our names mostly have their origins in Turkish, Arabic, and Persian languages. My name is originally Arabic but in Arabic countries you don’t have the female version of my name, usually only the male version. Then in terms of the architecture of the mosques here in Bosnia, if you see the old town in Sarajevo it reminds you very much of the Ottoman presence in Bosnia which is like the urban picture of many cities in Bosnia and so on and so forth. But an important thing to note, and what was important for the context of that time, the 19th century, is this very strong reformist thought. The scholars and the theologians of that time were asked to find new responses to the new circumstance of that time, to reinterpret the sources of Islam to find answers to what extent would Islam allow a Muslim to live under non-Muslim rule. We have one key document of that time from Azabagić he was as well later a Reis ul-Ulema after Hadžiomerović , and he issued this risala fi al-hijra as a response to the migration waves towards the Ottoman lands, where he in brief and I don’t know how much time I have left.

Ismail Royer: Keep going you’ve got about another seven or eight minutes please continue.

Dževada Šuško: Azabagić’s risala is very, very important because basically in his treatise on migration he confirms the possibility of Muslims living under non-Muslim rule. He uses sources of Islam. He uses verses from the Quran. He uses hadith to underline his argumentation. For the Bosnian Muslims in first place was not lose our religion, din. This was in the priority and there was this fear of having to give up the religion. So Azabagić was affirming life in the end of European Muslims and the non-Muslim rule. He was as well very much concerned that Bosnia would demographically lose its Muslim population. Many of his arguments went in that direction. Many Bosnian Muslims fled or migrated towards Ottoman land, usually being promised a piece of land and cattle and some help from the Ottoman state. But many of them had a very negative experience. We have here within the archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina witness reports of people who came back from the Ottoman lands, or came back on foot having spent all their money there and having to walk back home because they could not establish life in the Ottoman Empire. Perhaps this was of the reasons why Bosnian Muslims have this strong patriotism. I suppose perhaps we can state that throughout the coming times we have this column of that patriotism concerned to keep the territorial integrity of Bosnia, to keep the religion of Islam, and to the keep Bosnian language as the mother tongue. Next to establishing this institution of the Islamic Community, for them it was important to care for the education of their children, youth, to care for imams and sharia judges. At that point of time sharia courts were still kept. Austria-Hungary had a policy of dual institutions to keep the old institutions and to establish and introduce new institutions. Austria-Hungary had this policy, we can see one of the most impressive buildings in Sarajevo, the city hall Vijećnica which used to be a university library and was one of the first targets when during the war in the 1990s, where two million books and manuscripts were burned down. This Vijećnica was built, one would say, according to Islamic architecture but for sure not respecting Ottoman architecture because the Bosnian Muslims were supposed to gradually distance themselves from the Ottoman Empire from the south and from the Sheikh of Islam, and to have something indigenous which belongs to Bosnia only and which belongs to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Vijećnica that was built in what many called the pseudomoorish style. You can see such

buildings similar in Andalusia or in North Africa. It is clear why it was the interest of Austria-Hungary to establish an Islamic Community in Bosnia. The interest was as well to spread power and influence to control the religious education because during the Ottoman Empire, if you wanted to get a higher university degree you would have to go to Istanbul or somewhere else within the Ottoman Empire. Now theologians were educated in Sarajevo with the establishment of the Islamic Community, by establishing the first, which would be in translation, higher school for sharia judges, where theologians were educated in Bosnia under the control of the of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Today let’s say this first higher educational institution which was established during the Austro-Hungarian time continues until today as the faculty of Islamic studies here in Sarajevo. So we have this continuity from the Ottoman Empire until today and oriental languages could be studied in Vienna instead of going to the Ottoman Empire.

Ismail Royer: Dr. Dževada let me ask you really quickly, and please continue, but I wanted to ask you can you tell me what the relationship between the Islamska zajednica or the Islamic Community leadership, the Reis ul-Ulema and the Austro-Hungarian authorities was at this point? Was it a sort of co-option type of thing or was there an understanding? Or how did that work?

Dževada Šuško: It was a very close relationship with cooperation. Let’s say the first Reis ul-Ulema, he received an appreciation from Austria-Hungary for his loyalty and for his willingness to cooperate. Many others as well from our political and religious elite at that point in time were appreciated, for example Mehmed Dekapitano Bislupusuk. He was a rather political figure of that time but still as well very educated religiously. He was given the golden medal of the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy. He was actually the first Muslim to be appointed within the European aristocracy. We have these ulama, reformist theologians who were very close to the Austro-Hungarian Empire because in their rationale there was no alternative. We have to get along with Austria-Hungary because the Ottoman Empire did not have any more influence in southeastern Europe. They had abandoned us, so we have to face the new reality. We have to get along with the new reality. Also, the rationale of Azabagić which I forgot to mention, which came up now to my mind put it in simple words, that is as long as the ruler is just and as long as the ruler or the political system does not force you to abandon your religion, and as long as the ruler is respected by the majority of the population, and as long as you’re not hindered in practicing your religion, you must as a Muslim respect that political system. You have to expect respect for that ruler and you have to obey to his laws.

Ismail Royer: Thank you so much Jeremy do you have any questions?

Jeremy Barker: I think there is a lot to pick up on regarding that relationship between a religious person and government and what the obligations are within the state and where there’s freedom within that. Another way to say it is if the state does not forbid what God would command or command those that things that God would forbid, that provides the freedom to live within that that context and under the state.

Ismail Royer: What’s interesting to me is that nevertheless you still have a loss of Islamic order. You have a loss of ordering around Islam as the superior framework, and you have a replacement of that with in a way with Catholicism because the Austro-Hungarian Empire was not yet a nation-state. By the way there are many questions among Muslims regarding whether that is legitimate. It’s understood that that was the pragmatic necessity, but nevertheless does it represent some sort of loss or was it understood that way?

Jeremy Barker: Professor Jahić, maybe you can pick up on some of these themes and from your work as a historian of religion and culture as well as a former member of the House of Representatives, you have a lot of experience to bring to bear on this, both the contemporary issues but you also know the period around World War II and its influence on the Muslim community in Bosnia. Choose the starting point that you’d like and bring us into this conversation.

Adnan Jahić: Thank you very much Jeremy. Hello to everyone, good afternoon as-salamu alaykum. First of all I would like to thank the organizer for making this webinar possible and to say that I’m really privileged to be able to give a small contribution to better the understanding of the general topic. The idea of my presentation deals with the question how the Bosnian Muslim community responded to the emergence and politics of a homogeneous national state during the Second World War, namely the Independent State of Croatia (IC) which was a puppet nationalist state, established by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy in occupied Yugoslavia in 1941. As is well known for many years Bosnian Muslims have lived in the environment of living together with other peoples and religions within the multi-ethnic and multi-religious state formations from the Middle Ages to the kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Although this experience, I would say, should not be idealized. The facts tell us that the peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina have been accustomed to respecting the rights of others but they also expected the state to maintain an order that would protect law and peace as well as religious property and the other rights of its subjects. So the Independent State of Croatia, led by the extremely nationalist movement known as Ustaše provided nothing of these values. The Islamic Community and Bosnian Muslims first greeted and welcomed the establishment of the new state simply because of the fact that they hoped it would be better than the previous state, the kingdom of Yugoslavia. But actually, when they saw that this state had turned into an instrument of violence they were highly disappointed and reacted to the unbearable situation by signing the famous Muslim Resolutions, the so-called Muslim Resolutions in the autumn and winter of 1941. Although the topic of Muslim Resolutions in 1941 has been widely treated and discussed in both academic and broader social circles, it still I would say undoubtedly does not lose its importance and relevance, continuing to attract the attention of authors of various professional fields in order to understand the meaning and significance of Muslim Resolutions. It is important first of all to look at the political and social position of Bosnian Muslims, in today’s words, Bosniaks, in the newly framed state legal constellation after the disintegration and occupation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1941. There is no doubt that Bosnian Muslims in no other period of their recent history have been in such a critical and unenviable position as in the time of the quisling Independent State of Croatia, shortly IC. I will use this term with Bosnia and Herzegovina fragmented and forcibly integrated into the IC administrative order with an imposed creation identi

ty without basic political rights, with destructive nationalisms around them, whose conflict threatened the survival of their biological being, with their own elites who were not up to such critical and fateful historical developments. So this position can be actually characterized as a position of elementary political disenfranchisement. One nation, one community, depends entirely on the will of another nation and its leaders. So it’s totally incomparable with any period of their modern history. It is partly, let’s say, comparable to the situation in the first years of Austro-Hungarian rule when the only way to fight for their rights and interests was actually to send petitions to the ruler in Vienna, or in the first years of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes after 1918, when Bosnian Muslim religious and political leaders wrote letters to the Serbian general Stepan Stepanović and came out in the state council with requests to spare the lives and sanctity of the doorstep of Muslims who were exposed to ruthless terror and looting by the so-called comite, that means the robbers from Montenegro and other violent elements on both sides of the Drina river. However the fundamental difference was in the fact that after 1878 and 1918 there was peace in the country and the relations between the faiths and nations in Bosnia and Herzegovina and abroad regardless of class and civic antagonism were much different and more favorable than in 1941, when Bosnia and Herzegovina in the conditions of German and Italian occupation became the scene of a bloody conflict between extreme Croatian and Serbian nationalism with devastating effects on the lives of ordinary people and Bosnian society as a whole. So there is no doubt that the program of the Ustaše movement was actually one of the most disastrous projects ever attempted to be implemented on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina. For example, thanks to the occupier and especially the so-called wild Ustaše, divlje ustaše in the area of Bosanska Dubica over 50 percent of pre-war Orthodox population was slaughtered and annihilated in the villages of Drakulić, Šargovac, and Motike near Banjaluka. In just a few days the Ustaše killed and slaughtered, using agricultural tools, about 2 300 local members of the Orthodox population. So it is important to note here also that certain numbers of Muslims participated in these crimes, which were at least tolerated, if not planned and carried out by the Ustaše Croatian state. Some were voluntarily, I am talking about this participation, but in some places also forced by senior Ustaše commanders, thus exposing their compatriots to the danger of revenge by the Chetniks, meaning the bearers of the greatest Serbian ideology and all those who hold Muslims collectively responsible for the crimes of the Ustaše. Of course the suffering of Bosnian Muslims in some regions like eastern Herzegovina, Koraj Srebrenica, Višegrad, and Rogatica was certainly not only the revenge for Ustaše crimes but also the beginning of genocide against the Bosnian Muslim population who found themselves in the autumn of 1941, I would say, between the hammer and anvil of Chetnik extermination brutality and Ustaše genocidal policy with anti-fascist partisans who at that time were trying to build an alliance with Chetniks in their struggle against the occupiers and the Ustaše. So such was the position of Bosnian Muslims in 1941. The unbearable state of terror, oppression, lawlessness, and insecurity forced them to respond, and not only because of possible new pogroms against the inhabitants of Muslim settlements but also because Muslims began to doubt and fear that they would be actually the next victim of the Croatian Ustaše regime, after the extermination of the Orthodox Serbs. So the irresponsible speeches of certain Croatian officials highly contributed to this, but also the undeniable identification of the Ustaše movement with the traditional symbols of the Catholic Church in those newspapers. There were many articles according to which the IC should be exclusively a Catholic state. It was not only the Poglavnik Pavelić statement during his speech to some Orthodox converts from the great parish of Baranja that quote, “it is better if there is” he said “one religion in the state,” but also lots of other chauvinistic speeches of officials and supporters of the new regime to which Bosnian Muslims responded with characteristic sensitivity and complaints to their own representatives, I mean ministers and Islamic Community officials. So all of the above was actually in the background of the appearance of the Muslim Resolutions in 1941. It is very important to understand that these resolutions actually came out from the sort of objective historical perspective, and also that they actually originated in the political and social environment of local communities. They were conditioned by existing into religious relations and security situation and actually their creators were local Muslim leaders. So there was no sort of central Bosnian authority behind their appearance, although in the literature very often it is said that the resolution of the organization of Ulama al-hidaya of the 14th of august 1941, opened the door to voices against the current situation in the Ustaše state. It is interesting to note that actually hidayah first warmly welcomed the establishment of the IC and on the other hand, the leader of the Islamic Community that was raised Reis ul-ulema Fehim Spaho was very cautious in his attitudes towards the new state but still did not sign any resolution, believing that some sort of individual advocacy was a better way to protect Muslim rights. Let me say that my from my personal view there were many resolutions that were signed in different cities like Sarajevo, Tuzla, Prijedor and so on, but the strongest and most impressive was actually the Banjaluka resolution. It is quite specific when it talks about politics and methods of work and management in our region. So it leaves actually no doubt about the role of the Ustaše state and the Ustaše government in the crimes, which is completely logical given the scope of terror perpetrated by the Ustaše in the region of Bosniska Krayna and the role of some prominent Ustaše officials such as Viktor Gutić in inspiring, inciting, ordering, and approving crimes. So let me just provide the short quotations. So it specifically states “killing priests and other notables without trial and verdict, shooting and killing crowds, often completely innocent people women and even children, persecution and masses from home and bed of entire families with a period of one to two hours to get ready and deport them to the unknown places, the appropriation and plundering of their property, the demolition of places of worship, often with their own hands, forcing to convert to the Catholic faith. All these are facts which have astonished every true man and which have had the most uncomfortable impression to us Muslims.” Then in the continuation of the Banjaluka resolution, the specific motive is on the line which is in my opinion actually represents the most significant dimension of all Muslim Resolutions in general: “we never expected, let alone wanted, such methods of work in governance in our region. In our turbulent past we have not used such means even under the most difficult circumstances, and not only because Islam forbids it, but also because we have always believed that such methods of work lead to the destruction of public peace and order in every state and endanger its survival. We believe that such violence should not be perpetrated against even the worst enemy, because of the things that have occurred in our country we doubt that an example could be found in the history of

any nation in the world.” Let me at the ending part of this speech actually give a few words on the assessments of the historiography which is also a very important matter. Unlike some historical literature and journalism, critical historiography has raised serious questions about the background purpose and also the meaning of the 1941 Muslim Resolutions, to mention only Thomas Labdulic and Emily Greble. I think they rightly pointed out the relativity of concepts of law and injustice in these resolutions. From my personal point of view in assessing the Muslim Resolutions of 1941, it is very important to remain within the framework of the history of the Balkan peoples of the first half of the 20th century and not to neglect the models of collective thinking and action of their elites. So the experiences of the first Yugoslavia between the two World Wars showed what confessionally colored nationalism did to the idea of south Slavic unity. This reality was actually conditioned by inherited social and political barriers so the signatories of the 1941 Resolutions should be seen as members of a cramped, weak, and troubled community, repeatedly shocked by sudden historical plots and twists, and not as some fighters for universal human rights which were in their time, even in much more politically developed societies, just a hazy idea. In that sense it was not surprising that the signatories expressed, as one historian said, chauvinistic regret only for Muslim victims, but in those times, and I would say actually the question is whether it is much different today? Elites consider themselves authorized to stand up and advocate primarily for the interests of their own people and community, ethnic, political, or religious group, believing that there is someone else who would care for the rights of others, preoccupied with the idea that enough injustice had already been done to us and ours and that is high time now to take their needs and interests and as the priority. This part is very important. This could explain that after criticism of anti-Serbian demonstrations and calls for good relations between the religions, there were no reactions of Catholic and Muslim religious leaders to the repressive measures of the old Targaryen regime towards members of the Serbian community during the Great War, as it helps us also to understand the complete silence of the Serbian political, intellectual, and religious elite on the news of the terror and killings of Muslim residents of Podrinje, eastern Herzegovina and Sandžak in the early years of the kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. So the historian Thomas Labdulic asked why the Catholic Church in the Independent State of Croatia did not protest like the resolutions of Muslim intellectuals in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Archbishop Aloysius Stepinac did he points out intervene for the benefit of individuals and small groups of people but that never took, I think he is right, the form of an open and organized campaign across the country while at the same time many Catholic clergy generally, so to say, enthusiastically participated in forced conversions. The situation was no better on the Orthodox side either. The Serbian Orthodox Church has refrained from any protest against Chetniks crimes against Muslims, and so Labdulic expressed the opinion that actually many Orthodox and Catholic priests had invested, as he said, too much in building a new state, Yugoslavia, and the Independent State of Croatia to dare openly criticize and attack it. This was not the case with Muslims due to marginalization in the society of the Ustaše state regardless of the real intentions of the regime towards Islam and Muslims. Nevertheless I will conclude that no matter how much the meaning and value of these Muslim Resolutions were actually relativized by the narrower class and ethnic interests of their signatories and their unwillingness to give to the main condemnations the broadest civic meaning, I would say that these bold social acts undoubtedly remain a shining example of courage and responsibility of concrete people who pledged their names and integrity in a country under the Nazi occupation for a new order, without dangerous, bloody anarchy and religious and national hatred and exclusivity. That was their actually historical importance. Thank you very much.

Osman Softic: Thank you Professor Adnan. If you allow me just to ask a couple of questions in relation to Professor Adnan’s presentation. If I can just summarize quickly, it appears from your presentation, Professor Jahić, that the Bosnian Muslims, or at least the sections of the Bosnian Muslim community in the beginning welcomed the political change because they thought that what probably in their perspective appeared as the new world order at the time, will liberate them from the regional hegemony or oppression by the monarchy of the Yugoslav kingdom of Yugoslavia. However when they realized the veracity of the crimes and the atrocities that the agents of the Independent State of Croatia committed against the neighbors of different religions, particularly the Orthodox Serb population and the Jews and other minority communities, then they realized that they have to act. And they acted and there is no doubt this is an admirable and a historic record. It’s a historical effect and we’re proud of the Islamic Community leaders who took to themselves to initiate those resolutions. Now if I can get to my question. What I’m wondering is what do you think in your opinion, now coming back to reality now at our present time? I noticed in recent days or recent weeks there is a lot of criticism by the certain sections of the Bosnian ethnic communities, particularly from the Serbs for instance. They are very critical of the book which was written by British historian Marko Attila Hoare who is currently a professor of history at this Sarajevo School of Science and Technology, who emphasized the role of the Bosnian Muslims in the Second World War, and I believe he emphasized just as you did the positive role of the Muslim leadership, Bosnian leadership, political leadership, as well as the Islamic Community leaders. Do you think that there is a fear that threatens the reconciliation process in Bosnia and Herzegovina if these historical facts are emphasized? There is in my opinion a concerted attempt from some sections to actually annul or to dismiss these facts as inventions or a revision of the modern history of Bosnia and Herzegovina. What do you think? What is your opinion?

Adnan Jahić: When you speak about the importance of doing the historical research, I think it is from my point of view crucial to the reconciliation in this region, because especially when it is the case of the Second World War there is a lot nationalist agendas trying to present the history and the developments in the Second World War as they were not actually. So we have lots of problems because now we have a sort of one-dimensional view on the history of the Second World War in Croatia, in Serbia, in so as to say, in Bosnia also. You know, there is no one general perspective. That’s why I think that books like the one that you have mentioned of Marko Attila Hoare are very important. The other thing is that we do not have enough research in the archives. For example, the archive the best or the richest archive concerning the documents about the Second World War is in Belgrade, and it is called now the Military Archive of Serbia. It is very hard to penetrate, to get into this archive and without those documents it is practically impossible to research the Second World War. I would say that the lessons of the Second World War have not been received enough in these days, and there are lots of, so as to say, mythology concerning the victims, concerning the roles of some participants, and when you mentio

n Islamic Community, I would say that I have a sort of mixed perception. I’m currently writing a new book about the Bosnian Muslims in the Second World War, and I think we have to be sufficiently responsible and sensitive to some particularities concerning some elements of the Islamic Community. The Islamic Community was not a unified community and in each period the situation is the same. You had this al-hidaya current within the Islamic Community, you had the authorities or the Reis ul-ulema and ulema majlis and so on. I think Marko did a great job but also lots of other things have to be treated properly in the upcoming works.

Ismail Royer: Thank you for that Dr. Jahić. It raises a question to me and I’ll address this to both Dr. Šuško and Dr. Jahić. When did nationalism begin to play such an important part in the framework of Bosnia? We went from a period of the Ottoman Empire where nationalism was not was not very significant at all, it was not a phenomenon, to the spread of nationalism to the Balkans. It’s often said that Bosnian Muslims are ethnically Muslims more than they are religiously Muslims. That’s what you’ll often hear from people who don’t really necessarily know much better. Of course reality is much more complicated. How did Islam, or for that matter, Catholicism, with respect to the Ustaše, how did is how did religion become a subset of nationalism?

Dževada Šuško: Bosnia is not the exemption. Like the rest of Europe the rise of nation, states the rise of nationalism comes with the 19th century, the spring of nations all over Europe. Bosnia was not exempted from it. For example, all southeastern Europe, except for sure the Albanians, are dominantly a Slavic population, speaking Slavic languages, in our case the Bosnian language. In Bosnia’s case too with the rise of nationalism, the rise of nation states, particularly in the neighboring countries of Serbia and Croatia, we have now today in the 21st so-called constituent peoples: the Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs, going back to the medieval time of Bosnia. In Bosnia, independently of the religious identity, the people identified and were described as Bosniaks. We have even works from Serb authors from the 19th century talking of Orthodox Bosniaks, Catholic Bosniaks, or Muhammadan, Muslim Bosniaks in Bosnia. But the name Bosniak, which has been now reduced to the Bosnian Muslim community, only is an example of nationalist idea in Bosnia itself. So while the population, as I said, they the people here named themselves and were named Bosniaks. Then with the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, gradually the local Catholic population was instructed, particularly by neighboring Croatia and in schools, teachers were sent to teach the future generation that they are not any longer Catholic Bosniaks but Croats. The same happened on the Orthodox or Serbian side, that they were taught that they’re not any longer Orthodox Bosniaks but Serbs. Although this understanding that Bosniak is the term for all citizens in Bosnia remained until the Second World War. In the institute where I used to work we had a republication of a PhD dissertation from the University of Sorbonne, which dealt with the Sufi topic, not the political issue at all, but in the introductory part the author named the citizens of Bosnia, the people of Bosnia, as Bosniaks. This perception remained even during the First World War for example, when we mentioned Austria-Hungary, the military unit coming from Bosnia was the Bosniaken-Regiment. Within this Bosniaken-Regiment not only Muslim fought, but as well Orthodox and Catholics. They even wear the red test, the red hat which was a symbolic headdress head cover for Muslims only, but they identified it still with the Bosniak identity. So this nationalism has its roots in the 19th century, like in any other case, and we shouldn’t treat Bosnia always as something different from the rest. Usually the processes that happened here happened as well in the neighboring countries or in the rest of Europe. The same with the relationship of faith and religion. Bosnia has developed the relationship between the religious communities in Bosnia and the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A similar model like it is prevalent in other Western, or if you like European countries. You mentioned initially France. France is really the exception with this principle of laïcité. Here in Bosnia we have a secular state was never questioned by the Islamic Community, which never tried to abolish it. Not at all. It’s a secular system which was introduced with the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Islamic Community, like to other political society systems, adapted to its the new political system without giving up religious values and beliefs. Today in Bosnia we have a secular state, we have a constitution which sets the framework. Bosnia has adopted international conventions such as convention for the protection of human rights, European convention for the protection of human rights where religious freedom is as well an integral part. We have as well a specific law on the stages of religious communities and churches and religious freedom, which recognizes the relationship between the state and particularly the four traditional religious communities, which are the Islamic Community, the Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church, and the Jewish community. By the way the Jewish community has its roots and it was settled down in Bosnia during the Ottoman period, during the process of Reconquista in Spain. Not only the Muslims were expelled but as well the Jewish community, and they found refuge within the Ottoman Empire. Some of the Jewish migrants in that point in time settled down in Bosnia, and today we have a Jewish community in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Last year we celebrated actually the coexistence of Jews and Muslims in Bosnia. This is where Bosnia might be an exception and a good example of best practice regarding how Jews and Muslims got along for centuries.

Adnan Jahić: If I may add just a few words. I think that the role of religion and or the role of religious communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well in the Balkans should be treated properly and not idealized in any ways because you have the sort of positive and also sort of negative aspects of the activities of these of the religious communities concerning the process of, so as to say, differentiation, and also a sort of disintegration processes in the Balkans. Each religion and each religious community also represented a sort of tool of making a separate national identity in the Balkans and also in the ex-Yugoslav region. So when you speak about the non-existence of the separate Bosniak national identity, the question is what did the religious communities do or contribute to the destruction of Bosniak identity? Dževada actually explained the fact that the religions and religious communities helped destructing this integral Bosnian or Bosniak identity. So when we are speaking, we can speak about the tolerance, we can speak about good relations between common people within the religious framework, but we can also speak about the role of religious communities as the factor of putting people aside one from another. You know and many historians actually tried to explain this ambiguous role of religion in the Balkans, because the concept of nation in the Balkans cannot be understood properly while neglecting the religious factor in those processes.

Jeremy P. Barker: I think that’s an important point and very descriptive. Religious identity can play a role as a toxin and as a cause of chall

enges, or as a tonic, as what’s necessary. In many cases robust religious freedom and the relationship between those communities helps to ideally push the situation in one direction versus the other. I wanted to pick up on maybe the next period of time that hasn’t been mentioned thus far. It stood out to me in my first visit to Syria back in December. You have the architecture of the Bos Tarsha and the very Ottoman style and where it meets the West and it feels like you’re in Western Europe. But you walk a bit farther and you see Soviet style architecture and I wanted to pick up on the Soviet period and then emerging from that. What were the influences of that on religious identity and experience for the Muslim community in particular, through the Soviet period but then emerging from that as we come into the 90s 2000s? What was the influence of the communist presence in Bosnia?

Adnan Jahić: After World War II a secular system was introduced in Yugoslavia. Although the religion, the church was separated from the state the communist regime in its first years passed a couple of laws which aimed to marginalize religious communities, to weaken them materially and socially and also to reduce them to the sort of insignificant religious communities or, so as to say, insignificant civic associations. Well at the same time in order to survive, the Islamic Community had to adapt to this new state of affairs. It is also very interesting regarding the Islamic Community, that the reflection of its very unenviable position in those days it actually contributed itself to the weakening of the role of religion in society. For example madrasas and maktabs were abolished in Bosnia and Herzegovina in Yugoslavia, except for the Gazi Husrev-beg Madrasa in Sarajevo, and for some maktabs in mosques. The Islamic Community in those times officially claimed that it was actually normal and that maktabs and madrasas were obstacles to modern education and cultural progress for Muslims. However when we speak about this period of 45 years from 1945 to 1990 there is also one very interesting phenomenon that began to occur in those years. Under the influence of socialist and materialist ideology, some new interpretations emerged among individual members of the ulama in this period, which included basically a rationalist view of religion, religious and metaphysical concepts, and the role of the religion generally in the lives of Muslims. I would mention actually, as the main representative of this current, Husein Đozo, who was actually a true successor of Dzerma Ludin Caucevic, and his reform efforts in the first half of the 20th century. What happens after the dissolution of Yugoslavia from my personal perspective, I would say, that when the political and ideological pressure of the state on the Islamic Community disappeared, the Islamic Community generally speaking ideologically pluralized, while at the same time the trend of a sort of re-traditionalization of Islam began to strengthen. Today, in my opinion, the modern, contemporary interpretations of Islam in Bosnia adapted to the 21st century almost do not exist. Another one has gone back some hundred years in spiritual and ideological terms.

Dževada Šuško: I fully agree with what Dr. Adnan just mentioned. Indeed, like after the Second World War as well in other contexts, in other states where communist rule was established, first of all those who disagreed with communist ideology were brought to prison. It was a quite aggressive atheization of society, and of the political system in general. The Islamic Community was fully put under state control, so those who were leading the community at that time were usually obeying the new rule. They had to compromise themselves, but the state indeed, as Dr. Adnan mentioned, introduced several measures to control the community and to marginalize religion. Islamic books were forbidden, or the publication of new Islamic books. The publishing house was closed down, Sufi orders were as well closed down for a certain period of time. The girls’ part of the madrasa of the high school, which is we would compare today’s Islamic high school, was closed down so what could be closed down was closed down. What could be put under state control, was put into state control. Then in the 1970s we had a sort of liberalization. It became more comfortable. Mosques were then reopened again. What I would mention as a woman, and we have I guess as well other women who are watching our today’s webinar, the anti-fascist womens’ front organized public gatherings where Muslim headscarf-wearing women took off the headscarf as a sort of liberalization, as a sort of progress, to show that wearing a headscarf is something retrograde, something backward, and now taking off your headscarf in public is something progressive and something which shows progress. So this is, I think, very important. This period of communist rule, with the period as well of liberalization, Đozo Husein was indeed very important within the Islamic Community. We have this process of democratization and pluralization of Islamic practice, with opening up the borders and the intense exchange during the war, as well with modern technology, where now you have access to all kinds of interpretations of Islam, to all kinds of scholars, not only what Islamic Community publishes here in Bosnia in the Bosnian language. With democratization the Islamic Community regained its autonomy. So we have in Bosnia until today a working of the Islamic Community and religious communities in general. Church separation, but with cooperation. There is separation from the state but we are cooperating in certain issues where it is necessary, such as the interreligious council, which is supported by the state, where the four traditional religious communities are represented. As part of the democratization process, and I think this is interesting and where the Islamic Community differs from other communities in other dominantly Muslim societies, men who are given leadership mandates do not have a lifelong tenures. Even the Reis ul-ulema, even the Grand Mufti, let’s say, can be re-elected once for seven years as a maximum. Other leading positions only twice you can be reappointed. Within this time we have a legislative body, the parliament, where one third of the representatives are clerics, or if you like, employees of the Islamic Community, and the rest are civilians, the rest are people, members of the Islamic Community, who would like who work on legal issues within this body. We have an executive body, the so-called reacet where I’m employed within the department of foreign affairs and diaspora, working with the mosques and the imams in Bosnia and in our diaspora. Our diaspora is in North America, in the United States of America and Canada. In Europe our largest communities are in Germany and Austria, but as well in other European countries, and in Australia. The Islamic Community cares for the needs of those Bosnian Muslims who identify themselves as Bosnian, who identify themselves with the Islamic Community, and who are members. Every imam in Bosnia, in our diaspora, in our neighboring countries of Serbia and Croatia, is appointed by the Grand Mufti. The imam needs the approval from the Grand Mufti. This has been very significant in the last decade, with the attempt to impose a new practice of Islam in Bosnia, with the attempt to radicalize Bosnian Muslims who have adapted to living throughout these different civilizations and these different political systems, who have learned to have a rather an open-minded, peaceful interpretation and practice of Islam. This appointment of the Grand Mufti of the Reis ul-ulema, of the individual imams has shown to be a preventive measure for preventing radicalization and violent extremism, because we have this control mechanism. T

he Islamic Community runs six Islamic high schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina, three Islamic faculties, of which the faculty of Islamic studies was originally established during the Austro-Hungarian period in the late 1880s. We have two more Islamic faculties as well. So the Islamic Community is educating its religious scholars, its imams, its theologians, its religious teachers, and is controlling as well what is being taught in mosques. It is important that, just as during the Austro-Hungarian period, the Islamic Community cares for the endowments, for the foundations, for the waquf. This was really a fight, and we called it fight even during the Austro-Hungarian period. The Islamic Community wanted to be in charge of education, religious education, and be in charge of its foundations, and this has been kept until today. I think this democratic practice of how to organize an institution that deals with the teachings of Islam, educating Muslims, organizing Muslims, at home and in our diaspora is indeed something unique.

Ismail Royer: Dr. Šuško I was going to say that anyone who’s familiar with the way that the Islamic Community works in Bosnia, and the way that it maintains some level of control over, let’s say orthodoxy, is a very interesting phenomenon, and it’s able to do so without government interference. To me this is, and I’ve talked to many, many imams, representatives of Islamic authorities from the Arab world, and they can’t conceive of an Islamic leadership that does not involve government control. Their response to that is, well if we didn’t have government control, then there would be no way of preventing either extremism or various other types of unorthodoxy. So for the Bosnian Islamic Community, say, if some imam starts saying something that’s outside what the Sunni belief is, then you can just fire him. I was just in Utah, in Salt Lake City, and the imam there is appointed by the Islamic Community. This to me is a really interesting model and a very good model for how Islamic leadership in the Muslim world could become independent from government control. I think Osman you’ve got a question now.

Osman Softic: If I may just jump in with the two questions. I don’t know if we’ll have time. You mentioned quite rightly that these mechanisms of the institutionalized Islamic Community as an organizational structure really helped mitigate some of the serious challenges, such as the competing influences, especially in recent decades, with different countries vying for influence in the Balkans and particularly in the Bosnian context, struggling for the hearts and minds of the Bosnian Muslims. Still the Bosnian Muslims managed quite successfully to remain autonomous and their own without selling themselves to anybody else. What I would like to ask our respected professors, and they can both answer if they want, probably Dr. Dževada first in relation to the inter-religious council. I think this existence of the inter-religious or interfaith council of the religious communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina has probably an important role to play, and my second question is and this is where Professor Adnan can jump in as a as a legal scholar, is what do you think is the reason why the Islamic Community still has not succeeded to sign an official agreement with the state, and what are the obstacles? Two other religious communities, the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church have all have already done it.

Adnan Jahić: If I may say that Dževada is far much more competent to answer both the questions, but at the end I would if I may add some concluding remarks.

Dževada Šuško: My system broke down for a couple of seconds, so I did not understand your first question.

Osman Softic: The interreligious council and its significance in the reconciliation process, and the getting together between different religions, and why the there is no success so far in signing the agreement between Islamic Community and the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina?

Dževada Šuško: The inter-religious council is of utmost importance for the reconciliation process and for strengthening peace and security in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This is very important. There are lots of projects going on, even if there are sometimes some tensions among or between some religious communities. It is an important institution. We have to continue to cooperate. I think there is, and it is not my personal opinion, I know that this is the opinion of the Islamic Community and of the Grand Mufti, that there is no alternative to dialogue. So we always have to sit together to talk, to communicate, to find common ground, to find common projects, and to have peace and security in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This is always our goal. The inter-religious council as I said has representatives of the four traditional communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and is supported by the state. Many projects are supported by the international community, by individual embassies or by international actors. So we appreciate this very much and we think this would really harm peace in Bosnia if the inter-religious council would not pursue its task and its work. Regarding the agreement, this is a very important point. I didn’t want to mention it because it’s quite complicated initially, but I mentioned that within the state of Bosnia we have several legal frameworks, and one legal framework is the law on the legal status of churches and religious communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. An integral part of that law is that the state recommends that agreements are signed between the individual church or religious community and the state. That law was passed around 2006 and one year later the Catholic Church already initiated to sign that agreement. The goal is to meet the specific religious needs or the specific needs of the individual religious community to practice their religious, and for the practice of their members and adherents. Although the agency which signed that treaty between the Catholic Church and the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina was the Vatican in the end. So it’s an international agreement, signed by the members of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. We have a tri-party Presidency. It consists of three parts, one from each of the three constituent peoples, one Serb, one Croat, and one Bosniak. One year later the Orthodox Church as well launched negotiations to start to sign such an agreement and they did sign it eventually. The Islamic Community did not consider initially to sign the agreement because the community felt that religious freedom is guaranteed, that there is no need as the Bosnian Muslims make up the absolute majority. And there was just this feeling that there is no necessity to sign such an agreement. But then when the issue of religious classes in public schools came up, because once there was this public debate that religious classes in public schools should be abolished and should be removed from public schools, it became clear because one of the integral parts of such an agreement is that the religious community has the right to care for religious education or to appoint religious teachers and to publish religious textbooks which are going to be used in public schools religious classes. So this is when the Islamic Community realized how important it was to have this agreement. The Islamic Community is in negotiation and has been in negotiation with the state for several years. The neg

otiations were primarily about this. The agreements between the Catholic Church or the Vatican and the Orthodox Church, and the agreed agreement of the Islamic Community is to 90 percent almost identical, talking about that these are traditional religious communities, that they are autonomous, that they have the right to publish religious books, that they have a right to have their own media and so on and so forth. But then when it came to these specific needs of the Muslims, this is where the negotiation became very harsh. It’s about religious rights in the public space where you might have as an employee the right, let’s say, to take a break during the Friday Juma’ah prayer, the obligatory Friday prayer for men, that you have the right to perform your prayer if it is a prayer time during your work, a right to access halal food at your workplace or in the public sphere in general. It’s about having the right once in your lifetime to take a break to perform the pilgrimage the hajj. It is mentioned as well in the addendum, saying that that the workflow should not be hindered. Let’s say a surgeon who is doing his surgery, is I mean it’s human reasoning, will not leave his case and go to perform the prayer. I guess that this is clear to all of us. It’s as well about the visual identity of Muslims. I’m a member of the committee for religious freedom here within the Islamic Community, and we have cases where men wearing the beard were threatened that they would lose their job if they would not shave their beard. And we have a woman working for the military here who has decided to wear a headscarf, and she had a lot of trouble on her jobs just because of her headscarf. We have as well women who applied for a job with the headscarf who did not get the job just because of the headscarf. So we have these cases regarding the visual identity of Muslims, forming an integral part of the agreement. This is now in the last phase, that this agreement should be signed by all three members of the Presidency. Currently it’s just not on their agenda, so in the end it is a political issue. We have to wait for the time until it becomes politically suitable to get the agreement on the agenda get it signed. So the negotiations are over. Everything is set. Now we need the political willingness of two members of the Presidency to sign that agreement.

Ismail Royer: Thank you so much. That last question seemed to go really directly to the heart of what we wanted to talk about today, and there is so much more that we need to talk about. I have a long list of questions that we are not able to get to, but we’ll just have to do this again if both of you are willing to do that. We’re also looking forward to having our in-person conference in Sarajevo which we are hoping to do in October and we of course would love to have both of you there. So we want to thank again on behalf of the Religious Freedom Institute all of you, Dr. Dževada Šuško and Dr. Adnan Jahić and Osman Softic for being with us and we really hope to be able to do this again with you in order to get to the rest of the questions that we didn’t get to. Jeremy do you want to say anything to close us out?

Jeremy P. Barker: Thank you, it was a really enlightening conversation as we look at the historical but then these contemporary issues and what it looks like to live out our faith in in a pluralistic world and the challenges but opportunities that come from that. So thank you to each of you for sharing your experience and we look forward to doing this again in this format, perhaps but in person and in Sarajevo before too long we hope.

Ismail Royer: I think we can all learn a lot from the resiliency and the intelligence and the genuinely beautiful spirit of the Bosnian people. It’s something that is really admirable and it’s a jewel of Europe.

Jeremy P. Barker: Thank you and to learn more about the work of RFI, visit us online at rfi.org thanks to you all.

THE RFI BLOG

Myths of Religious Nationalism in America and Abroad

France’s Olympic Hijab Ban Violates International Law And Exacerbates Tensions

RFI Briefs USCIRF on Lessons from 25 Years of U.S. Designating Religious Freedom Violators

Thought Police: Protecting the People from Prayer

A Religious “Delaware”: Establishing a State Haven for Religious Corporations

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Challenges to Religious Freedom in Iraq and the Critical Need for Action

Public Bioethics & the Failure of Expressive Individualism

Religious Liberty in American Higher Education

Scotland’s Kate Forbes and the March of Secularism