As the Hobby Lobby case, which challenges the HHS contraceptive mandate as a violation of the free exercise clause, comes before the Supreme Court, we ask what the outcomes may mean for religious freedom, American business, and corporate employees.

By: Ira Lupu

The Hobby Lobby litigation has stirred up a vital national conversation about the religious freedom of businesses in the U.S. The idea of corporate conscience is hardly new, and a distinction between corporate moral conscience and corporate religious conscience is not defensible. To the extent the existence of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) has helped stimulate that conversation, the Act is a national good.

Unfortunately, RFRA is structured in a way that reduces the visibility of the costs that religious freedom may impose on others in the marketplace. Litigation under RFRA typically involves the government opposing a religiously motivated person, asserting burdens on her religious practice. In many circumstances, relieving religious persons of legal duties will impose only trivial or highly diffuse costs on other persons. For example, in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal (UDV), the Supreme Court unanimously upheld a claim by a religious group that restrictions in the federal Controlled Substances Act on the importation of hoasca tea, a hallucinogenic substance used in UDV sacraments, violated RFRA. Crucial to UDV’s victory was the government’s inability to convince the courts that the group’s use of hoasca tea presented a danger of either illicit trafficking or harm to human health.

In Hobby Lobby, by contrast, relieving the business of legal duties would impose focused and significant harm to third parties, not directly represented in the litigation—the many female employees of these firms, and the many more female dependents of all their employees. It is hardly surprising that employees have not come forward to join a lawsuit against their employers, but judges should not lose sight of the fact that a RFRA exemption for Hobby Lobby would mean that its thirteen thousand employees’ health insurance would not cover emergency contraception and intra-uterine devices.

Supporters of Hobby Lobby try to minimize these costs, by arguing that 1) most women use contraceptives already, so the coverage gap won’t matter; 2) the government will ride to the rescue and provide these contraceptive services for women covered under the Hobby Lobby policy; and 3) a RFRA victory for Hobby Lobby won’t make any women worse off than they were before the Affordable Care Act.

All three arguments are deeply flawed:

-

As developed in the Guttmacher Institute’s amicus brief, most women use contraceptives but a great many women cannot afford the safest and most effective contraceptives. Hormonal IUD’s are among the most expensive and effective of all, and emergency contraceptives may be essential to prevent pregnancy from rape. As Marty Lederman has explained, ensuring the availability of these products will inevitably reduce unintended pregnancies and thereby reduce the incidence of surgical abortions.

-

The government is under no obligation to cover these services for Hobby Lobby employees if the company wins its lawsuit. Moreover, its employees will not be eligible for subsidies if they purchase health insurance, which would include the missing contraceptive coverage, on the exchanges.

-

As Professors Schragger, Schwartzman, and Tebbe have pointed out, a Hobby Lobby victory will indeed make these women worse off in both a legal and material sense. The Affordable Care Act adds a mandatory term to every employment contract in private businesses across America; if an employer provides health insurance, it must include specified pregnancy prevention services. This is conceptually no different than the requirement that an employer pay into the Social Security system, or pay at least the minimum wage. (The Supreme Court has rejected claims of religious exemption from both of these employer responsibilities.) A RFRA exemption from Affordable Care Act duties would thus alter the employment contract, and benefit Hobby Lobby at the direct expense of its employees.

This last point should be fatal to Hobby Lobby’s RFRA argument. As an amicus brief by Frederick Gedicks and other church-state scholars has argued, and Bob Tuttle and I elsewhere develop, the Supreme Court has insisted that “courts . . . take adequate account of the burdens a requested [statutory] accommodation may impose on non-beneficiaries [here, the employees].” That is a constitutional principle, rooted in the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. When employers make RFRA claims that significantly burden their employees, that principle should control the outcome.

Ira C. Lupu is the F. Elwood and Eleanor Davis Professor of Law Emeritus at the George Washington University Law School, which he joined in 1990.

This piece was originally authored on March 23, 2014 for the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

THE RFI BLOG

The Horrendous and Maddening Antisemitism in New York City

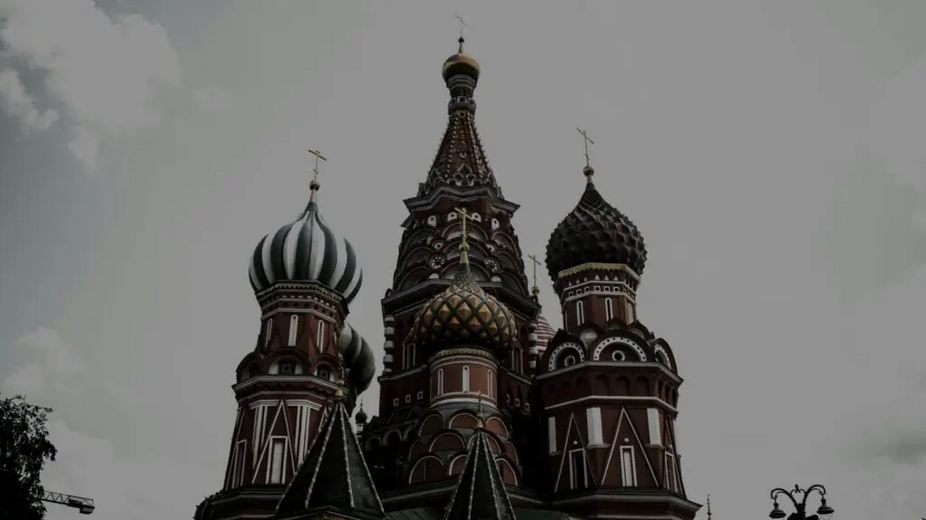

Religion, the ‘Russian World,’ and the War Against Ukraine

Religious Freedom Is Back on the UK’s Agenda

Be More Faithful, Become More Resilient: An Invitation to Religious Institutions

How Soccer Reveals Different Meanings Of ‘Secular’ In France And The US

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Public Bioethics & the Failure of Expressive Individualism

Religious Liberty in American Higher Education

Scotland’s Kate Forbes and the March of Secularism

70 Years of Religious Freedom in Sweden: Prospects and Challenges