Religious freedom has often been referred to as the “first freedom” in America’s constitutional order, but some scholars have argued that liberalism requires that religious freedom not be treated as special or unique in the pantheon of human rights. In this post series, scholars and individuals from all different disciplines and faiths try to define religious freedom and explain why it is a right of particular importance.

By: Asma Uddin

Religious freedom is the right of individuals and groups to be free from state interference in matters of faith. It is sometimes confused as having to do with relationships among private entities, but in fact the legal definition requires government involvement. And freedom from government coercion makes it clear why religious freedom is important—no one wants the government telling them what to do or feel, much less dictating one’s spiritual life.

As a religious minority in America, the right to religious freedom is particularly important for me because without it, individuals with strong biases against my faith who also have the ability to influence the government would deny me the most basic of religious rights.

Consider, for example, a challenge in Tennessee when an Islamic center sought to expand its facilities. Their construction materials were burned, and there were a lot of protests. Mosque opponents claimed in court that Islam is not a religion, and therefore shouldn’t have the protections of the First Amendment. It’s an accepted fact of American society and law that religious persons have the right to build houses of worship. To circumvent that clear legal fact, anti-Muslim activists argue that Islam cannot be afforded any religious freedom protection because it is not a religion.

Another issue is the anti-sharia laws that about half of the states have proposed. There are three types of anti-sharia laws. One specifically mentions sharia as a legal tradition and singles it out for disfavor. This type of legislation was introduced as a ballot measure in Oklahoma, and was approved by voters, but ultimately blocked by the courts. The second type lists a number of different legal traditions that are disfavored, and sharia is one of them, along with halacha, canon law, and karma. The third and most common type bans all “foreign law.” The fact is, sharia has never posed a problem in the United States, and even if it had, we already have a Constitution that precludes judges from getting involved in substantive religious issues. Proponents of anti-sharia laws are essentially proposing a solution to a non-existent problem.

And while solving a problem that doesn’t exist, these laws, if enacted, would create religious freedom problems for Muslims—restricting even the most basic ways that we order our lives according to our religious principles. For example, consider an employment contract where an employer allows a Muslim employee to work different hours during the month of Ramadan. If the employee tried to enforce that contract in court, the judge couldn’t even consider what Ramadan is. Of course judges can’t delve into theological debates, but normally they can engage in fact-finding to better understand the terms of a given contract. Anti-sharia laws would prevent even these types of basic sharia considerations.

Importantly, these simple considerations protect acts that are profound in purpose—our religious practices are essential to our quest for truth. To navigate that journey freely is the reason religious freedom is so important.

Asma T. Uddin is the founder and editor-in-chief of altmuslimah.com, a legal fellow with the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, and an international law attorney with the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty.

This piece was originally authored on April 14, 2014 for the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

THE RFI BLOG

A Call to End Anti-Semitism on America’s College Campuses

The Horrendous and Maddening Anti-Semitism in New York City

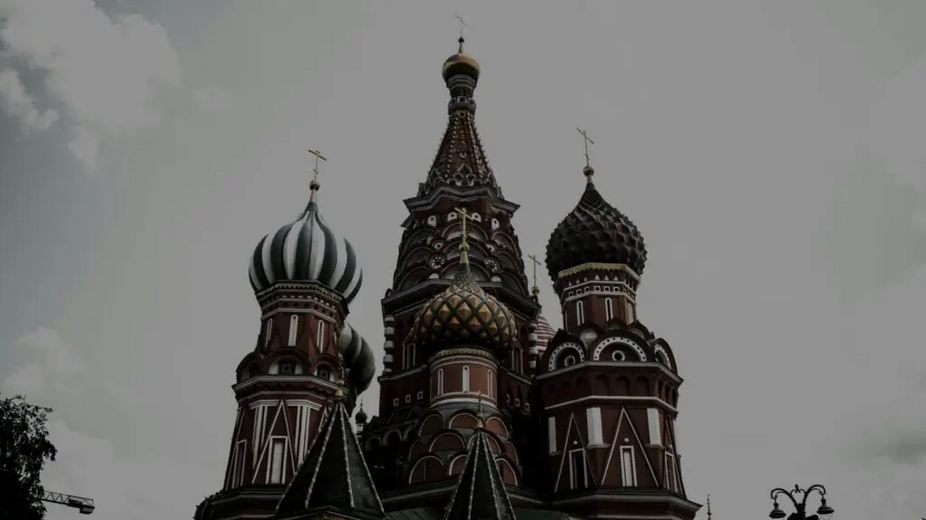

Religion, the ‘Russian World,’ and the War Against Ukraine

Religious Freedom Is Back on the UK’s Agenda

Be More Faithful, Become More Resilient: An Invitation to Religious Institutions

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Public Bioethics & the Failure of Expressive Individualism

Religious Liberty in American Higher Education

Scotland’s Kate Forbes and the March of Secularism

70 Years of Religious Freedom in Sweden: Prospects and Challenges