Religious communities in Iraq, especially religious minorities, have suffered enormously over the past year. Longstanding sectarian tensions between Shiites and Sunnis deepen the crisis in Iraq, which is disrupting the entire Middle East. This week contributors are asked to evaluate this situation as a crisis of religious freedom. They address the following questions: What explains the success of ISIS in Iraq? Why do sectarian tensions exist? What can be done to resolve this conflict and prevent similar ones in the future? What role might US or international religious freedom diplomacy play?

By: Andrew Doran

In January 2009, a few days before President Barack Obama was sworn into office, a colleague at the State Department emailed our office a speech by future Ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice. The speech pointed to poverty as the primary cause of violent extremism. What, I asked my colleague, might account for the presence of so many wealthy and educated among the ranks of so many terrorist organizations? He had no response.

Since 2003, as America has found itself engaged in what is arguably the most religious region in the world, a handful of secular thinkers, perhaps most notably David Brooks and Jurgen Habermas, have admonished the West’s aggressively secular public culture to reconsider its approach to the phenomenon of faith. With few exceptions, these calls have been ignored. America has proved to be unequal to the task of engaging the reality of faith in any meaningful way.

At a time when Muslims are a growing demographic in the West, religion is being driven to the margins of the public life of the West. At the same time, thousands of Western Muslims have flocked to the Middle East to fight for ISIS. It is a twisted faith that drives these young men and women to the Islamic State—but it is faith nonetheless. (This author cannot improve upon Graeme Wood’s “What ISIS Really Wants” piece in the Atlantic. It merits reading and rereading.) ISIS is, of course, a military threat, as it enters its second year as a peculiar political entity. But ISIS also presents the West with a series of cultural challenges.

The West has proved incapable of presenting desirable alternatives to the extremism offered by Islamist militants. Put simply, few in the West’s public life have demonstrated a competence—or even a serious desire—to engage believers. This is a painful irony for many Americans in light of the fact that religious freedom is a concept deeply rooted in America’s history and traditions. (Even the least religious among America’s founders, Thomas Jefferson, believed religious liberty to be foremost among the Enlightenment era’s achievements.) However, this tradition has been challenged—and largely bested—by an intensely secularized public culture, hostile in particular to Christianity, the dominant faith of the West. Many leaders and intellectuals simply do not hold the right to religious freedom in terribly high esteem. Competing and conflicting values have emerged, and these take greater precedence, even in the conduct of US foreign policy.

This “secularist habit” was captured perfectly in the tragically banal remark by a State Department spokesperson recently that “jobs” are the key to fighting ISIS . This remark is symptomatic of a foreign policy establishment and public culture that lacks much-needed dimension, which would aid in understanding what animates ISIS’s constituent parts.

ISIS is an outgrowth of the escalating fundamentalism, extremism, and violence that has emanated ideologically—and with an abundance of funding—from the oil-rich Gulf states in recent decades. This Wahhabi-influenced fundamentalism, once peculiar to Arabia, and hostile to the outside world, emerged from virtual isolation to heavily influence Sunni Islam in the last century. In recent decades, the abundant wealth from the Gulf has employed many thousands in terrorist professions that threaten not only Americans but minorities and moderates across the Middle East—with the PLO, with Al-Qaeda, with Al-Nusra, and with ISIS. (Compounding the irony and tragedy, hundreds of millions more have gone to purchase influence at America’s leading academic institutions and think tanks, and with lobbyists inside the Beltway.) As America has fought a global conflict against terrorists, it has done little to stop their funding sources.

America’s recent misguided policies—clinging to ill-suited nation-state paradigms, backing sectarian leaders, naïve belief in procedural democracy as a panacea—may have created the environment in which ISIS could capitalize on sectarian divisions and ultimately thrive, but they did not create ISIS and cannot easily defeat it. Given this pattern, and the foreign policy establishment’s a lack of desire (and competence) to engage in the area of religion and culture, it falls on others in the public square to step forward. It is here that the West’s civil society—institutions and individuals—can take a more prominent role, particularly religious leaders and institutions.

The West’s public culture has responded to Islam’s growth by either insisting that Muslims conform to secular society (Europe) or by way of insincere placations, designed to mollify Muslims in hopes that they will gradually abandon their old beliefs in favor of secular materialism (America). Thus far, the former model—Voltaireans crying, “Écrasez l’Infâme” (crush the infamous)—has failed spectacularly. Christian institutions and intellectuals in the West have, however, fostered meaningful engagement, acknowledging both shared beliefs as well as differences. These encounters offer hope that a shared vocabulary for political and cultural discourse can be forged. Whether this will lead to what Habermas called “an autonomous justification of morality and law (that is, a justification independent of the truths of revelation)” remains to be seen—though it should be noted that this is not, or need not be, synonymous with the abandonment of belief. Indeed, this was the basis on which diverse believers in America were able to establish a nation constituted on pluralism.

Perpetual violence in the Middle East is no more a foregone conclusion than is peaceful pluralism in the West. Furthermore, democracy cannot bring about stability, prosperity, and freedom in pluralistic societies without a developed sense of the common good. The common good must be preceded by and predicated upon an acknowledgement of a common experience and common values. This ought to be at the heart of cultural engagement in the West and the Middle East—for religionists and secularists alike. But before any commonalities can be ascertained, the West’s public culture must acknowledge that religion, faith, and spirituality animate the overwhelming majority of people on the planet, particularly those in the Middle East.

Andrew Doran lives in the Washington, DC area and writes about religion and human rights in the Middle East, with a particular focus on the region’s original Christian communities.

This piece was originally authored on March 12, 2015 for the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

THE RFI BLOG

A Call to End Anti-Semitism on America’s College Campuses

The Horrendous and Maddening Anti-Semitism in New York City

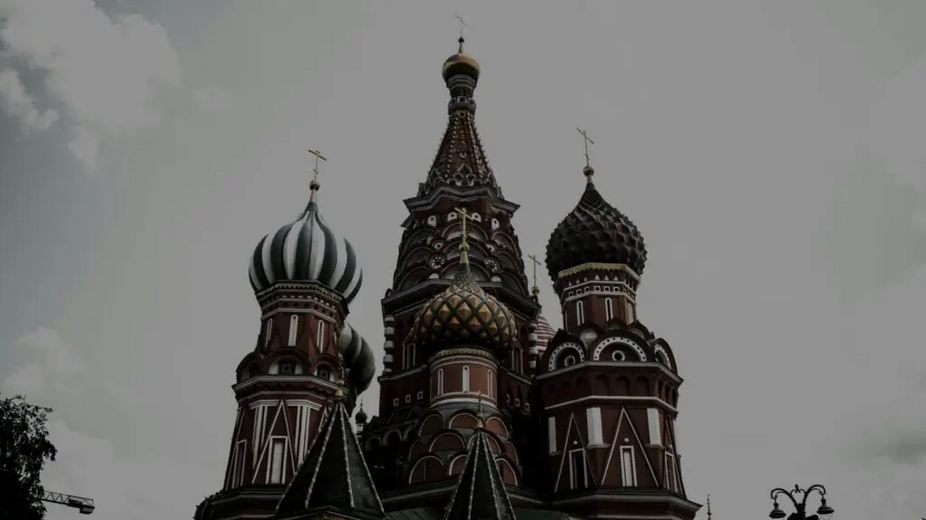

Religion, the ‘Russian World,’ and the War Against Ukraine

Religious Freedom Is Back on the UK’s Agenda

Be More Faithful, Become More Resilient: An Invitation to Religious Institutions

CORNERSTONE FORUM

Public Bioethics & the Failure of Expressive Individualism

Religious Liberty in American Higher Education

Scotland’s Kate Forbes and the March of Secularism

70 Years of Religious Freedom in Sweden: Prospects and Challenges